- Home

- Patrick Ness

Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing Read online

From the reviews of Topics About Which I Know Nothing:

‘Here are 10 short fictions, each of which works as a showcase for Ness’s highly quirky imagination … Each story is a tasty titbit, to be savoured briefly before moving on to the next one. What makes these stories so delightful is that there actually is something very substantial at work behind them, however airy they seem at first. They’ll lodge in the mind.’ Guardian

‘Ness’s first collection brims with inventiveness and creative audacity.’ Daily Telegraph

‘Ness’s take on the absurd and offbeat is sharp, intelligent and funny.’ Time Out

‘Remarkable, an extraordinary, yet utterly convincing creation.’ Scotsman

‘Sparkling humour … Ness has a wonderful imagination: creative, unpretentious and pleasingly bonkers.’ Metro

‘Very, very funny … a unique comic manifesto from a very talented newcomer.’ Daily Express

For Vicki Burrows, Belle of Puyallup

We’ve got so many tchotchkes,

We’ve practically emptied the Louvre.

In most of our palaces,

There’s hardly room to manoeuvre.

Well, I shan’t go to Bali today,

I must stay home and Hoovre

Up the gold dust.

That doesn’t mean we’re in love.

The Magnetic Fields

Contents

Cover

Title Page

From the reviews of Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction to the New Edition

Implied Violence

The Way All Trends Do

Ponce de Leon is a Retired Married Couple From Toronto

Jesus’ Elbows and Other Christian Urban Myths

Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?

Sydney is a City of Jaywalkers

2,115 Opportunities

The Motivations of Sally Rae Wentworth, Amazon

The Seventh International Military War Games Dance Committee Quadrennial Competition and Jamboree

The Gifted

Now That You’ve Died

Notes and Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction to the New Edition

You always love the awkward child best, don’t you?

I get asked all the time (by teens in particular) what’s my favourite book of the ones I’ve written. I always answer that it’s the same as asking your parents if they have a favourite child: you know they have one, but they’re never going to admit it.

But Topics About Which I Know Nothing has a bit of a special place for me (not least that it taught me never to have a comedy title; funny the first time, but 500 times later…). Because these are all stories I wrote on the real expectation that no one would ever read them, and if that were true, then I could just have loads of fun amusing myself and seeing if I could get away with murder. With some of these, perhaps, it’s a close call.

‘Sally Rae Wentworth’ (even with its slightly imperfect grasp of geography) is still one of my secret favourite children. ‘The Gifted’, too – a rare instance of autobiographical writing (to an obvious point). ‘Quis Custodiet’ goes all the way back to my college writing classes with T. C. Boyle (if heavily revised), and ‘Sydney is a City of Jaywalkers’ is my first published piece of writing ever.

I love short stories and have kept on writing them. The new story in this collection, ‘Now That You’ve Died’, was written as a commission for the Royal National Institute of Blind People for ‘Read for RNIB Day’ (readforrnib.org.uk, which gets many more books into the hands of blind and partially sighted people). It was recorded as an immersive play, so imagine it in complete darkness, read to you in the terrifying and majestic tones of Christopher Eccleston.

In fact, that’s a good way to imagine pretty much any story, including the ones here. The original notes at the end thank the good and fine people at the much-missed Flamingo imprint, and I remain forever grateful to them for giving my awkward child such a good home.

London, 2014

implied violence

1

‘Implied violence,’ says the boss, ‘is our bread and butter.’

He means implied violence is what we sell, which it isn’t, we sell self-defence courses over the phone, but the boss likes to think in themes. He’s talking to the new girl, Tammy, which sounds American to me. I’ll have to ask Percy.

‘I don’t like to say we need to frighten our customers,’ says the boss, looking down at Tammy who is looking right back up at the boss, ‘but let me put it this way: we need to frighten our customers.’ This makes the boss laugh. Tammy laughs as well, too loud and too long. I look over to Maryam from Africa who meets my gaze.

There are only three of us, now four, who work in this little room, but we all wear nametags. Mine says my name, Maryam from Africa’s says hers, and Percy’s says his, but I notice that Tammy’s says ‘Terrific Tammy’. I look back at Maryam. She’s noticed it, too. She rolls her eyes as Tammy’s laugh just goes on and on.

2

On one side of me sits Percy. Percy is a very large bloke who falls over a lot. ‘I have an inner-ear problem,’ he says. Percy calls himself my mate.

On the other side of me is Maryam from Africa. Maryam from Africa is from Africa. I’m not sure which part, because I didn’t think you were supposed to ask. I’m not sure how to pronounce her name exactly either, because she says it in her accent and you can’t really ask her to repeat it. She frowns all the time but is not a mean person and doesn’t mind, I don’t think, that I just call her Maryam. She must be about fifty or so, but I wouldn’t be surprised at anything in a twenty-five-year range above or below that.

The three of us sit in a line facing one wall of our room, Maryam by the door, me, then Percy by the window. It’s one long desk with a computer, telephone and headset for each of us, but dividers separate us so we can have privacy to talk to potential customers. Behind us, there used to be only a wall, but now they’ve put Tammy at a card table against it. There isn’t very much room, so Tammy’s facing the window, and our backs are facing her side.

Why did they put her in here? There’s only room for three.

‘There’s only room for three,’ whispers Percy, but he has to lean towards me to do this and he falls off his stool. ‘I have an inner-ear problem,’ he says to Tammy and the boss, standing back up. ‘It affects my balance.’

3

‘Everyone here has a sales quota,’ says the boss. ‘It’s not a bad one, not a very high one, but it’s important that you meet it each week.’

Tammy nods. I don’t like the way she nods.

‘Because if you don’t,’ the boss puts his face close to Tammy’s, ‘we’ll have to send you to the end of the hall.’

Tammy laughs. No one else does. The boss smiles, but it’s not a laughing kind of smile.

‘And what’s at the end of the hall?’ says Tammy, still thinking it’s all for fun.

‘Only people who don’t meet their quota ever find out,’ says the boss.

‘And no one’s returned to tell the tale?’ Still smiling, still laughing.

‘I’m sure you’ll meet your quota just fine.’

Tammy’s forehead wrinkles a bit at how seriously the boss says this. She opens her mouth again but then closes it.

‘You’ve already met your colleagues, yes?’ The boss gestures towards the three of us on this side of the room. We all nod.

‘They introduced themselves this morning when I came in,’ says Tammy.

&

nbsp; That was only because we were discussing why there was a card table with a new computer, a new phone and a new headset crammed in the corner where Percy used to slide his chair back when he needed a few minutes’ break. In walked Tammy. The room was too small not to say hello.

‘Boss?’ says Percy.

‘Yes, Percival,’ says the boss.

(‘Everyone calls me Percy,’ Percy said to Tammy this morning.)

‘I’m wondering if Tammy’s going to be, you know, comfortable.’

‘Comfortable?’ says the boss.

‘Yeah, in that small corner, like,’ says Percy, looking at the floor, scratching the back of his neck. ‘It’s usually three to a room, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, Percival, you’re correct,’ says the boss, still with the not-laughing kind of smile. ‘It is usually three to a room, but just now we haven’t an extra space to slot Tammy in.’

‘All the other rooms are full?’

‘All the other rooms are full.’

‘No one’s gone to the end of the hall lately,’ says Tammy, already trying to make a joke. No one laughs. Tammy doesn’t notice.

‘It’s only temporary, Percival,’ says the boss. ‘I trust you’ll make our newest sales representative as comfortable as your colleagues made you on your arrival.’

Maryam and I ignored Percy for a week. He replaced Karen, who had gone to the end of the hall. We hadn’t really liked her, but we were surprised she hadn’t met quota. It really isn’t a very high quota.

‘Of course, boss,’ says Percy.

‘Good,’ says the boss. ‘If you have any questions, Tammy, I’m sure these three will be more than happy to help. I’ll let you all get to work.’ He leaves without looking at anyone. Maryam from Africa gives a ‘hmph’ to the whole thing.

4

‘What you have to consider,’ I say into my headset, ‘is what would a woman like yourself do if an intruder broke in one night when you were on your own with the children?’

‘I’d call Emergency Services.’

‘What if he cut the phone lines?’

‘I’d let my rottweiler do what rottweilers do.’

‘What if he’d brought minced beef with poison in it to put your rottweiler out of commission?’

‘He’s very persistent, this intruder.’

‘They always are, madam. I assure you, it’s not a laughing matter.’

‘I’d spray him with mace.’

‘You’ve left it in the car.’

‘I don’t have a car.’

‘You’ve left it at your friend’s house when you were showing her how to work it.’

‘I’d scream.’

‘He’s taped your mouth while you slept.’

‘After he poisoned my rottweiler and cut the phone lines.’

‘There’s been a rash of similar crimes in your area, ma’am. I’m only reporting the facts.’

‘Do you even know my area?’

I check the list. There’s no town name, but luckily I recognise the dialling code.

‘Derby, madam.’

‘Listen, this horror show has been very amusing, but I really must—’

‘What if he went for your children first and made you watch?’

‘That’s not funny.’

‘As I’ve said, madam, it never is. We offer self-defence training for the entire family.’

‘My daughter is five.’

‘Never too young to learn where to kick.’

‘It’d frighten the life out of her.’

‘I beg to differ, madam. Knowing a few basic moves might boost her confidence right at the time she’s about to enter school. Think about bullies, madam.’

‘Five, for pity’s sake.’

‘Most karate black belts start at three, madam.’

‘You’re making that up.’

I am. ‘I assure you I’m not, madam. One of the major positive points that clients have told us is that the self-defence classes have given them the appearance of confidence, and over 90 per cent have never even been forced to use their training.’

‘And that’s a selling point, is it?’

‘An armed world is a safe world, madam.’

‘I suppose so …’

‘Why not make your world a little safer, madam? Why not do yourself and your daughter, no matter how young, the service of being able to face the world with one more resource?’

‘Anything to help me sleep at night, is that right?’

‘That’s right, madam. Couldn’t have said it better myself.’

5

‘So what exactly is at the end of the hall?’ says Tammy.

We’re eating our lunches. The company doesn’t have a canteen, so we have to eat at our desks. I have a cheddar and ham sandwich that I make five of on a Sunday. By the smell of it, Maryam from Africa has a cold curry. Percy seems to have just pickles. His wife sometimes forgets to go shopping, he says. Tammy has gone outside to the sandwich shop down on the corner and got herself some kind of leafy salad and a fruit drink. We spend all our mornings talking on the phone, so lunch is usually a quiet affair. Not for Tammy, apparently.

‘It is what the boss says it is,’ I say.

‘All he said is that only people who don’t meet quota know what it is,’ says Tammy.

‘Exactly,’ I say.

‘That doesn’t make sense,’ she says.

‘It is what it is,’ says Percy, who has to steady himself with one hand when he looks up to say this.

‘Is it metaphorical, like?’ asks Tammy.

‘No, it’s just down that way,’ says Percy. He jerks his thumb in the right direction.

‘I mean,’ says Tammy, openly laughing at Percy, ‘that it’s just words the boss uses to motivate us. Implied violence. Like in our sales pitch.’

‘No,’ I say, ‘it really is just down that way.’

‘But that doesn’t—’

‘You meet your quota, then you never find out,’ interrupts Maryam from Africa. Her accent is a hell of a thing, foreign and stern, like being shouted at by a vampire maid. ‘Can we eat in silence, please? I hear enough chitter chatter all day long without having my digestion interrupted by nonsense of this sort.’

6

The self-defence classes we sell have no connection with this company. We’re just the telesales firm that the self-defence people hired to push their product. I’ve never been to a class. I’ve never even seen a brochure. Neither have Maryam from Africa or Percy for all I know. So far, Tammy hasn’t asked, and I’ll bet it’s the sort of thing she would ask about, so I’m guessing that maybe she’s seen a brochure or been to a class. It would figure.

7

‘Should we invite her to the pub?’ says Percy.

‘Who?’ I ask, though who else could he be talking about?

‘Tammy.’

‘Good God, no,’ whispers Maryam from Africa.

‘It’s rude not to,’ says Percy.

‘It’s rude to ask questions all day,’ says Maryam. ‘If you invite her, I’m not coming.’

‘You never come,’ says Percy.

‘I might today, if you don’t invite her.’

We prepare ourselves for an awkward moment when the day ends, but Tammy just bags up the jumper she’s slung over the back of her chair, waves bye, and leaves.

‘The cheek,’ says Maryam.

8

I bring two pints of bitter and one pint of lager to the table. The lager is for Maryam from Africa. It seems surprising that she drinks lager, but I suppose there’s no reason she shouldn’t. I get the drinks every night, even when it’s just me and Percy, because Percy can’t be trusted to carry anything. He’s all right once he’s standing or once he’s sitting; it’s the in-between that’s tricky, and that includes leaning. The management of the Cock & Cloisters have even barred him from handling small glasses of spirits.

‘Cheers, mate,’ says Percy. Maryam from Africa nods a thank you. Percy and I each take a swig from our b

itters. Maryam downs half of her pint in one long, graceful draught. It’s almost beautiful. She dabs her lip with a serviette and says, ‘I don’t like this new girl.’

‘Me neither,’ I say.

‘She’s not so bad,’ says Percy.

‘You say that about everyone,’ I say.

‘You say the boss isn’t so bad,’ says Maryam.

‘He isn’t,’ says Percy.

Maryam looks at me with eyebrows that say ‘point proven’.

‘And what kind of a name is Tammy for a grown woman?’ she says.

‘I reckon it’s American,’ I say, ‘but she doesn’t sound American.’

‘It’s South African,’ says Percy. ‘Short for Tamara.’

We stare at him.

‘How d’you know that?’ asks Maryam.

‘I asked,’ says Percy.

‘When?’ I say.

‘On the afternoon break,’ he says. ‘You were in the loo. Maryam was on the phone to her mum. It was just me and Tammy, so I asked. Polite conversation.’

Maryam hmphs again.

‘Hi everyone,’ says Tammy, suddenly appearing at our table from the cigarette haze of the pub.

‘You left before we could ask you along,’ says Percy, fast, before the rest of us even take in who Tammy is.

‘That’s all right,’ says Tammy. ‘I’d agreed to meet the boss here anyway.’ She points towards the bar, and sure enough, there’s the boss holding what looks like a pint of Guinness and a G & T. Maryam from Africa sighs and starts scooting over to make room for Tammy and the boss.

‘No need,’ says Tammy. ‘We’re sitting over there with some of the workers from the other rooms. What am I saying? I’m sure you know them better than I do.’

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

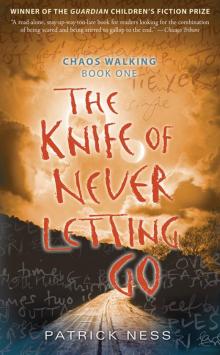

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

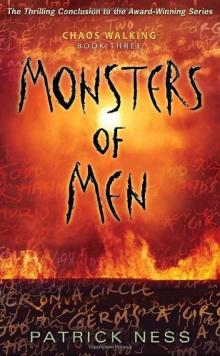

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

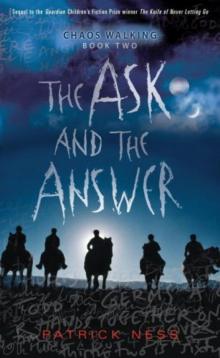

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

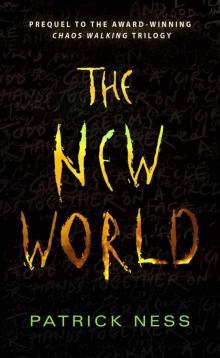

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking