- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Stone House

The Stone House Read online

Dedication

To James, Guy, and

Dame Margaret Rutherford

Contents

Dedication

One: Help Me

Two: Dandelions

Three: Rumours

Four: The Girl in the Window

Five: It’s All a Matter of Practise

Six: The Early Hours

Seven: Storm Front

Eight: View from the Attic

Nine: Faceless Alice

Ten: Greasy Spoon

Eleven: The Crossing

Twelve: Stranger on the Inside

Thirteen: Don’t Look

Fourteen: Leave Now

Fifteen: The House is Angry

Sixteen: Memory Box

Seventeen: Dreamweaving

Eighteen: Sentient Nightmares

Nineteen: Mr Alan F. Turnpike of Meadow Row

Twenty: The First Visit to Constantine Oliver

Twenty-One: A Touch of Wist

Twenty-Two: Dreamweaving Again

Twenty-Three: Running by the River

Twenty-Four: Phenomena

Twenty-Five: Constantine Oliver Ltd

Twenty-Six: Nightwatching

Twenty-Seven: False Security

Twenty-Eight: Splitting Up

Twenty-Nine: The Bed

Thirty: The Cellar

Thirty-One: The Attic

Thirty-Two: Somebody at the Door

Thirty-Three: Amira

Thirty-Four: Intruders

Thirty-Five: Concentrate on the Web

Thirty-Six: Miss Quill is the New Black

Thirty-Seven: Q&A

Thirty-Eight: The Door

Thirty-Nine: Back to the Old House

Forty: The Answer

Forty-One: Waking Up

Forty-Two: Arachnophobia

Forty-Three: The Bone Spiders

Forty-Four: The Papers

Forty-Five: The Lost Letters

Forty-Six: The Vault

Forty-Seven: The Reckoning

Forty-Eight: Reunion

Forty-Nine: Refuge and Revenge

Fifty: The Stone House

Back Ad

About the Authors

Books by Patrick Ness and A. K. Benedict

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

ONE

HELP ME

You know that abandoned house round the corner?

Garden rammed with dandelions, weeds reaching through the gates like gnarled hands? Stay away. No, really, STAY AWAY. It wants the lonely, the lost, the vulnerable. It wants you.

If I’d stayed away, I’d be home right now doing normal evening-type stuff like eating Shreddies from the packet and hacking the Pentagon. Instead, I’m trapped inside the stone house, screaming at the cobwebbed glass. I know, I know, I was warned. ‘Don’t go near,’ Mum said. She didn’t say why. Why doesn’t anyone say why? It’s all meaningful looks and ‘take my word for it’, not facts. I like facts. Facts, I can handle. Facts such as ‘some snails have hairy shells’.

That’s a good fact. You can hold on to facts like hair clings to the shell of the Trochulus hispidus. If you don’t have facts then fiction slips in.

Rumours cling to this house like ivy, but what’s inside is far worse. Its halls are stalked by nightmares, its nightmares stalked by whatever is keeping me here. If you see me at the window, send help. We don’t have much time. The stone house is alive and growing more powerful. Whatever you do, stay away. It’ll never let you go.

TWO

DANDELIONS

Earlier that week . . .

Tanya leans against Coal Hill’s gates. Ram’s late. He said he’d be out of training by five. It’s now twenty minutes past, and hot. Unseasonably hot, even for the time of year. The kind of hot that makes you check for sweat patches. The kind of hot where sweat patches join forces into one giant sweat patchwork. The kind of hot where you definitely don’t want to be waiting to help someone else with his homework. But he’d insisted she talk it through with him on the way home. And, typically, having made the plan, a plan she’d dropped everything for, he’s forgotten all about it.

Tanya kicks at one of the dandelion clocks growing through the cracks in the pavement. Its seeds scatter. There were already lots in the air, carried by a slight breeze. She picks another at the base of the stem and holds its fuzzy white head to her lips. It takes three puffs to disperse: three o’clock. Not even close. Some clock.

A stray seed brushes her cheek. Others land in her hair, just in her line of vision. She picks one out and examines it. It’s kind of cute. It looks like a tiny umbrella, spokes splayed. She looks it up. Turns out they’re called ‘filamentous achenes’. Fancy name for a seed. She’ll call it Brian.

Minutes pass. Still nothing back from Ram. Bet he’s forgotten or bumped into someone more important. She sends another message: ‘I’m off’.

Tanya walks away, squinting into the sun. She’s broken her new sunglasses. Again. Lucky they were only a fiver at the market. She sat on them while arguing what should have been a winning point with Charlie. It kind of undermines your case when you jump up and say ‘arsecakes’. Miss Quill said that she wasn’t to use that particular argument in the exam.

Tanya doesn’t have much luck with sunglasses. She has no idea how Ram manages to keep his designer ones pristine, no idea how he, or anyone else, achieves pristine anything. Too much effort. She’s seen April with the Nair tube, watched with a mixture of horror and fascination as the egg-sandwich-scented cream made the hairs crinkle up and shrug away from the skin.

A long way off, an ice-cream van sings. It’s a welcome sound, but if the last term has taught her anything, it’s that you can’t trust innocuous things like ice cream. What kind of alien would drive an ice-cream van? One that needs a cover story and easy access to ice—a snow monster who toppled through the Rift. She never used to think like this. Everything is now possible, other than Ram turning up on time.

Tanya looks around then slowly turns 360 degrees. This isn’t the right estate. Towels and geraniums, flags and clothes hang outside flats but she doesn’t recognise any of them. Mrs Cartwright’s collie usually meets her with a lick by the playground—but this is a different playground. An indifferent tabby flicks its tail across hot tarmac.

She’s gone the wrong way. Somehow her feet have taken her in the other direction, through another estate, other streets. Feet do that. Stupid feet. It must be the heat. Now she’ll have to circle round. Always go forwards, even if it’s to go back. There’s only one way, unless she wants to go by the canal, and the only reason to go there is if you want a spare shopping trolley, tetanus, or to play Count the Condoms. The other way, though, will take her down a certain street on which a certain building stands. It’ll be fine, Tanya tells herself as she rounds the corner. You’re being silly. It’s only an old stone house.

THREE

RUMOURS

The house stands on its own at the end of the road. It must be at least eighteenth century and looks old and incongruous next to the divided terraces and posh new-build apartments, as out of time and place as if it had been lifted up by an unlikely London tornado and plonked down in an East End street. She’d probably find the withered limbs of a local witch sticking out from underneath if she dug around in the rosebushes. Three storeys high, peeling purple and grey paint on stone—it’s the kind of house the Addams Family would shake their heads at, telling the estate agent, ‘It’s not for us, bit too gothic.’

If the rumours are true, then kids have visited and gone missing, and others have died. You’d think that’d make it the perfect place for teenagers to dare and date each other but most stay away. Last time Tanya was here, she’d s

tepped inside the porch and felt so cold and alone that she ran out and didn’t come back. Until now.

It’s one of those places that rumours stick to, like filamentous achenes to your hair. It can’t be that bad. And it looks like it’s going to find another owner, at last. There’s a SOLD sign in the front garden, weeds growing up to its hips. The rusting gates have been unlocked as well, although you can still hardly see the path running up to the front door.

Trees loom in the back garden, placing the pavement in front of the house into shadow. It feels like the only cool space in London today. She feels an urge to sit down in the grass, disappearing from view of the road. She’d better get home, though. Homework to do.

As Tanya walks away, she sees something move in a window. Getting closer to the railings, she looks up. In the top left window, a face presses against the glass. A young woman. Her fists hit at the window but make no sound.

Her mouth opens in a silent scream.

FOUR

THE GIRL IN THE WINDOW

She saw me. I know she did. Most people walk by quickly, never looking up, and even if they do, their eyes skim over me. They don’t want to look at my face. They don’t want to know. But she wasn’t afraid, not in the way they are. I shouted out to her and she stared straight at me. Even when she was walking away, she kept looking back, looking at ME. I could cry. I am crying and I thought I didn’t have any more tears left.

I’d like a friend. I used to have friends in Damascus, and then there were kind people who helped me on the long journey here. Now I only have the house and its nightmares.

I used to think I was really lucky. I had a wonderful time up to the age of eight or nine, living with Baba, Ummi, and Yana when she was a toddler, all grabby hands and baby-teeth smile. I went to school and was a good scholar, particularly at English. Baba taught me how to get plants to grow from a seed and dance towards the light, and Yana planted her dolls upside down, saying their long hair were roots.

That was before the war affected everything, and then luck turned against me, whispered when my back was turned, and now I am here, alone. I mustn’t wish the girl back. If she does return, she might catch my bad luck. She might never leave.

Like me.

FIVE

IT’S ALL A MATTER OF PRACTISE

The knife gleams in Miss Quill’s hand. She sharpens it even more, then turns the handle in her hands. It’s heavy, made from rare Kalthagon stone that reacts to body temperature. She aims it at the black paper silhouette attached to the back door.

The front door opens. Charlie and Matteusz walk in, laughing.

The knife zings into the silhouette’s head.

‘That’d hurt,’ Charlie says.

‘Certainly sting,’ Matteusz replies.

‘Definite inconvenience,’ says Charlie, walking over to the fridge.

‘I’m practising,’ she says. ‘Distractions are not welcome.’ Placing the knife back in its sheath, she takes a larger knife from the leather case and polishes it.

‘You could keep your knife-throwing to the bedroom,’ Charlie says. ‘Wait, that doesn’t sound right.’

‘The kitchen is the place for knives,’ Miss Quill says.

‘It’s just that it’s not the most relaxing thing to come home to,’ Charlie says. He takes out the vat of orange juice and pours two glasses.

‘When we’re no longer in mortal danger from an interplanetary or interdimensional threat, then I won’t practise in the kitchen,’ Miss Quill says.

‘That’ll be never, then.’ Charlie hands one of the glasses to Matteusz and follows him to the stairs. ‘We’re going to start on the small mountain of homework you gave us, then we’re going out.’

‘Next time it’ll be a mountain range,’ Miss Quill says. Miss Quill puts the kettle on. She has papers to mark and classes to prepare and perpetual darkness to fight. She’s going to need coffee.

Upstairs, she hears them walk across Charlie’s bedroom. A chair is scraped across the floor, a thump of a textbook on the floor. The surprising thing, given her experience, is that they do actually study after school. She’s passed an open door and seen them lying on the floor, books open, pens poised. Unless they are very quick at moving when they hear her coming up the stairs. She’s not sure what she’d rather—scholastic diligence or deception skills. Both are useful in warfare.

She can hear them laughing, even over the boiling kettle. He smiles so much more now. He’s too relaxed. Relationships do not further any cause; they diminish your fight, make you less strong by yourself. She pours hot water onto the ground coffee and watches it swirl. There’s an expression here for what it feels like to fall for someone: ‘go weak at the knees’. Why would you want to be weak anywhere?

The young people in her charge are so young and full of optimism and need to cling to each other. Not her. She doesn’t need family or memories or anything that holds her back. All she needs is coffee and the means to fight.

She throws the large knife at the silhouette. And another. Two more. Each knife finds a place in its heart.

Not that it has one. Shadows don’t have hearts.

SIX

THE EARLY HOURS

Tanya stares at her ceiling. It’s four a.m. She’s hardly slept. In theory that means she’s grabbed bits of non-REM sleep but not enough to be rested. She should know, she’s spent hours reading up on the sleep she isn’t having. Not that she can concentrate. She can’t stop thinking of the girl in the window.

She’s probably got it wrong, she must have. What if the girl wasn’t saying ‘help’, but ‘hello’ instead? It’s within the realms of possibility, and these days those realms are gargantuan.

She turns on her side, facing the window. The light is already pressing against the curtains. She’ll wait till six. That’s an almost OK time, isn’t it? Ram’ll probably already be up by then, squatting and flexing.

She sets an alarm on her phone. Maybe she can get just a little bit of sleep. The outline of the stone house window flashes against her eyes when she closes them.

Several hours later, Tanya’s in the classroom with Charlie, Matteusz, and April, half an hour early for class. Not even nine in the morning and it’s already hot. It’s lasted for more than a day so obviously the media have declared it a heat wave.

Charlie and Matteusz are looking at something on a phone.

‘Go on then,’ April says. ‘You said it was important.’

‘I’m waiting for Ram,’ Tanya says. ‘He said he’d be here.’ It took an hour of begging and wheedling over DM but he’d promised in the end.

Ten minutes later, Ram ambles through the door.

‘Nice of you to join us,’ Charlie says.

‘Isn’t it,’ Ram replies. ‘I’d rather be doing anything else at all but, no, I’m stuck inside with you.’

‘Charming,’ Tanya says. She then tells them what happened last night, right up to seeing the face at the window.

‘How could you see that from where you were standing?’ April asks.

It’s a reasonable question. She’d ask it herself if she hadn’t been there. But she had been. And that’s what she saw. ‘I just could,’ she says.

‘You said it was shadowed,’ April says, ‘and it was very hot yesterday.’

Tanya bites back rising anger. ‘I didn’t make it up.’ April shrugs. She’s got one of those little battery-operated fans that don’t do much. It’s got a reassuring whir and wafts her hair. She has very waftable hair.

‘No one’s saying that,’ Ram says, leaning back in his chair. ‘Not exactly, anyway. We’re implying it.’

‘What did the police say?’ Matteusz asks, paying attention at last.

Tanya sighed. ‘They said they’d send someone round. They hadn’t by the time I’d left. I waited as long as I could. I had to go home at some point.’ She knew she was justifying it to the girl left in the house, not to them. Tanya had gone back this morning and stood outside the stone house. It felt as if it was ca

lling to her, pulling her in. It felt sad down to every stone. There was no sign of the girl in the window. She could still be there, trapped in that room. ‘I’m going back after school today. Come with me, you’ll see.’

‘I can’t tonight,’ April says, checking her diary. ‘Got two committee meetings.’

Charlie and Matteusz look at each other. Matteusz bites his lip.

‘You’re trying to think of a reason why you can’t go, aren’t you?’ Tanya says.

Charlie shrugs. ‘You saw someone in the window of a house. It’s hardly invading alien levels of panic.’

Tanya’s certainty begins to slip. ‘I’m not saying it’s life or death. Not yet, anyway.’

‘I’m just thinking there’s plenty going on without looking for trouble,’ Charlie says.

‘I’m not looking for trouble, I’m just—never mind. What about you, Ram? What’s your excuse this time?’

Miss Quill bustles through the door. ‘What are you doing here?’ she asks. ‘Has April infected you with slightly unsightly keenness? Or have you all been replaced again? Tell me I don’t have to find an authenticating gun at this time on a Tuesday morning.’

They all look to Tanya. Clearly it’s her call on whether to tell her. ‘We’re just . . .’ Tanya searches for a reason. Any reason. Nothing is coming. She doesn’t want to tell her the truth. Miss Quill won’t believe her any more than the others.

‘Helping me with my homework, Miss Quill,’ Ram says. ‘I couldn’t get the hang of it myself.’

Miss Quill stares at them all. ‘If it’s wrong then you’ve all got a problem with it,’ she says. ‘And we can go over the whole thing again.’

They groan.

‘Can’t you take it easy on us, Miss Quill?’ Ram asks. ‘It’s too hot to think.’

‘You think this is hot? Try thinking on the back of a fire stallion while riding through the flame lake of Kabal. Too hot to think indeed,’ she mutters, taking out a textbook.

‘We could find somewhere shady to work,’ April suggests.

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

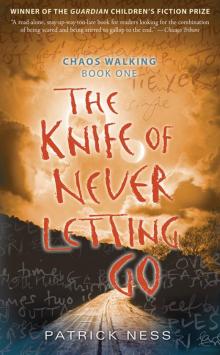

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

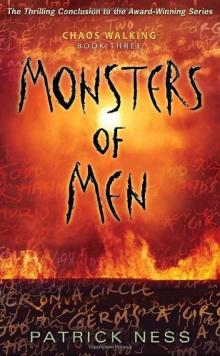

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

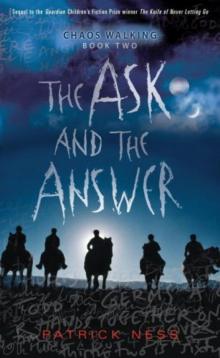

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

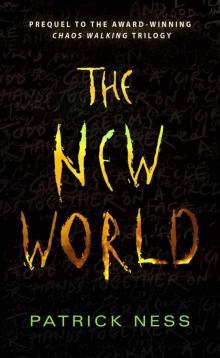

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking