- Home

- Patrick Ness

Burn

Burn Read online

Dedication

For Kim Curran,

golden soul

Epigraph

King Salamander, that’s his name

A desert maker, that’s his game

The benign Cremator, branding iron in his hand

Eager and willing to torch the land

—Siouxsie Sioux

Burn, baby, burn

—The Trammps

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part 1

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Part 2

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Epilogue

About the Author

Books by Patrick Ness

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part 1

One

ON A COLD Sunday evening in early 1957—the very day, in fact, that Dwight David Eisenhower took the oath of office for the second time as President of the United States of America—Sarah Dewhurst waited with her father in the parking lot of the Chevron gas station for the dragon he’d hired to help on the farm.

“He’s late,” Sarah said, quietly.

“It,” said her father, spitting on the oiled dirt, hitting the cracks of a frozen puddle. “Don’t call it by its name. Don’t tell it yours. It. Not he.”

This didn’t address the question of the dragon’s lateness. Or maybe it did, in her father’s sternness, in the spitting.

“It’s freezing out here,” she said.

“It’s winter.”

“Can I wait in the truck?”

“You’re the one who was so eager to come with me.”

“I didn’t know he’d be late. It would be late.”

“You can’t trust them.”

Then why are you hiring one? Sarah thought, though knew better than to say. She even knew the answer: They couldn’t afford to pay men to clear the two south fields. Those fields had to be planted, and if they were, then there was a chance—a small one, but a chance—that they wouldn’t lose the farm to the bank. If a dragon spent a month or so burning the trees, carrying out the ash and remnants, then maybe by the end of February, Gareth Dewhurst could be turning the charcoal over with a pair of cheaply hired horses and the plow that was thirty years out of date. Then perhaps by April, the new fields would be ready for planting. And perhaps that would be enough to hold off the creditors until harvest.

Such had been the overwhelming, exhausting thought of both Sarah and her father in the two years since the death of her mother, as the farm slid slowly beyond the ability of two people to run and further and further into debt. The worry was so strong it had shoved their grief to one side so they could work every hour her father was awake and every hour Sarah was not at school.

Sarah heard her father breathe out, long, through his nose. It was always his preamble to softening.

“You can drive home,” he said, quietly, back over his shoulder.

“What about Deputy Kelby?” she asked, her stomach tensing as it always did at the thought of Deputy Kelby.

“Do you really think I’d be meeting a hired claw if I didn’t know Kelby was off duty tonight? You can drive.”

She was five feet behind him but still hid her smile. “Thanks, Dad,” she said. At nearly sixteen, she was a few months shy of being granted a license by the great state of Washington, but a lot of things got overlooked for the sake of farming. Unless it was Deputy Kelby doing the looking. Unless you were Sarah Dewhurst being looked at, with her skin so much darker than her father’s, so much lighter than her dearly departed mother’s. Deputy Kelby had thoughts on these issues. Deputy Kelby would be only too happy to find Sarah Dewhurst, daughter of Gareth and Darlene Dewhurst, illegally behind the wheel of a farm truck, and what might he do then?

Sarah pulled her coat tighter around her, tying the belt. It was her mother’s coat and she was already outgrowing it, but not by enough to find the money for a new one. It strained across her shoulders, but at least it kept her warm enough. Almost.

As Sarah put her hands back in her pockets, she heard wings.

They were an hour from midnight—the Chevron was closed, only security lights on—and the sky was bitter cold and sloppy with stars, including a spill of the Milky Way across the middle. This part of the country was famous for its rain, though more accurately for its endless gray days. This night, though, January 20, 1957, was clear. The three-quarter moon was low in the sky, bright but a supporting player to the specks of white.

Specks of white that now had a shadow cast across them.

“It won’t hypnotize you,” her father said. “That’s an old wives’ tale. It’s just an animal. Big and dangerous, but an animal.”

“An animal that can talk,” she said.

“An animal without a soul is still an animal, no matter how many words it’s learned to lie with.”

Men didn’t trust dragons, even though there had been peace between the two for hundreds of years. Her father’s prejudice wasn’t uncommon among people his age, though Sarah wondered how much sprung from the way the articulate, mysterious creatures so comprehensively ignored men these days, save for the few willing to hire themselves out as labor. In Sarah’s generation, though, it was hard to find a teenager who didn’t also want to be one.

This particular dragon was flying in from the north, which Sarah liked to think meant it had come from the great dragon Wastes of western Canada, one of the few natural landscapes left in the world where dragons still flew wild, still held their own societies, still kept their own secrets. She knew this was fanciful. Canada was nearly two hundred miles away, the Wastes a further two hundred beyond that. Besides which, the Canadian dragons had withdrawn official communication with men a decade before Sarah’s father was born. Who knew what they got up to in the Wastes these past fifty years? The individuals who still hired themselves out as labor gave no answers, if they even knew. This one was probably only coming from another farm, another place of grubby, poorly paid hire.

It flew over them.

He, thought Sarah. He flew over them. The only reason she didn’t think She was because her father had slipped when he first mentioned the hiring. “It’s not illegal,” he’d said, which Sarah knew, “but there’ll be trouble no matter what. We keep quiet until he’s already working and no one can stop him.”

Sarah was unsure what had happened in the intervening week to move so firmly from he to it.

Beyond the light of the gas station, the dragon remained a silhouette as it circled, but even so, Sarah was surprised by its size. Fifty feet from wing tip to wing tip, possibly sixty.

The dragon was small.

“Dad?” she said.

“Hush, now.”

They watched it fly over them once more, then take off again into the sky. This meeting place wasn’t so surprising, nor was the hour. Enough light and civilization to make the man feel safe, enough darkness and lack of other humans to make the dragon feel the same, what with everything her father had rightfully said about potential trouble. Even so, this dragon was clearly more cautious than most of its kind.

When it finally landed, she saw why. She also saw why it was so small.

“He’s blue,” she said, breaking several of the rules her father had set down.

“I won’t tell you to hush again,” he said, not turning around, for his eyes were only on the dragon now.

The dragon was blue. Or a blue, Sarah corrected herself, and of course, not actual blue but the blue of horses and cats, a dark silvery gray that tinged into blue in the right light. What he was not was the burnt blackish red of the Canadian dragons she’d occasionally seen working farms or flying over the mountains in the distance, making their trips to who knew where for who knew what purpose.

But a blue. A blue was Russian, at least originally, in heritage. They were very rare; Sarah had only seen them in books and was more than a little surprised she hadn’t heard any local rumors of this one. A Russian dragon was also troubling for other reasons, what with Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union, threatening to annihilate them pretty much every week these days. Dragons didn’t get involved in human politics, but having this dragon on their farm wasn’t going to make the Dewhursts any new friends either.

It had landed just outside the ring of light from the gas station sign, the ring of light Sarah and her father stood well inside. The ground hadn’t shaken when the dragon settled—a gingerly step to the dirt from the air as it stopped its glide—but it did shake as the dragon came forward now, its head and long neck angling down low, the claws at the end of its wings hooking into the ground at each step, those great wings flaring on either side, making itself look bigger, more threatening.

When it finally came into the light, she saw it only had one eye. The other was scarred over, indeed seemed to have rope-like stitching holding it shut. The surviving eye led the rest of its body toward them until the dragon stopped and inhaled two big gusts of breath. Sarah knew it would do this. Their noses were sharper than a bloodhound’s. It was rumored they could smell more than just odor, that they could smell your fear or if you were lying, but this was probably the same old wives’ tale about them being able to hypnotize you.

Probably.

“You are the man?” it said. The words rumbled from so deep in its chest that Sarah almost felt rather than heard them.

“Who else would I be?” her father replied, and Sarah was surprised to hear a buried note of fear there. The dragon’s eye narrowed in suspicion. It clearly didn’t understand her father’s answer, something her father saw as well. “I am the man,” he said.

The dragon looked him up and down, then cast its eye over Sarah.

“You will not speak to her,” her father said. “I only brought her as a witness, since that’s what you require.”

This was news to Sarah. A witness? Her father had made it seem like coming along had been her own irritating idea.

The dragon kept its head low but arched its neck, looking for all the world like a snake about to strike. It brought its nose close to her father, so close it could have eaten him in a single snap.

Though that rarely happened anymore.

“Payment,” it rumbled. A word, not a question.

“After,” her father said.

“Now,” said the dragon, spreading its wings.

“Or what? You’ll burn me?”

Another low rumble from the dragon’s chest, and Sarah panicked for a moment, wondering if her father had gone too far. This dragon had lost an eye. Perhaps it didn’t feel bound by the—

Then she realized it was laughing.

“Why does the dragon no longer kill man?” the dragon asked, a smile curling the ends of its mouth.

It was her father’s turn to be confused. “What?”

But the dragon answered its own question. “Society,” it said, and even in the nonhuman (and for that matter, non-Russian) accent, even in its lack of a soul, Sarah could hear the amused bitterness with which it spoke the single word. “Half,” the dragon said, negotiating now.

“After,” her father said.

“Half now.”

“One quarter now. Three quarters after.”

The dragon considered, and for a brief moment its eye was on Sarah again. It can’t hypnotize you, she reminded herself. He can’t do that.

“Acceptable,” the dragon rumbled, and sat back on its haunches, awaiting the quarter payment. Gareth Dewhurst turned to his daughter and gave a small nod. They had expected this, and Sarah went to the truck, opened the passenger door, and reached into the glove compartment. She pulled out the small shiny fingerling of gold her father had formed by melting down his cheaply made wedding ring. It was all they had. They had nothing left to pay the dragon with at the end of his labor, but her father had refused all of Sarah’s attempts at solving that worry. “It’ll be taken care of,” was all he said. She assumed this meant melting down her mother’s silver-service heirloom set, hoping the dragon would take the lesser metal, knowing it probably would.

But what if it refused? What if it took badly to being cheated? Though on the other hand, what choice did it have in the end? Even deputies who weren’t Kelby wouldn’t care all that much about a dragon being underpaid. Still, it didn’t sit well in Sarah’s stomach. Not much did. It was where she kept all her anxiety. And there was a lot these days.

She brought the small sliver of gold over to her father. He nodded at her, at her bravery, she thought, as he took it from her. He held it up for the dragon to sniff, which it duly did, in an intake so strong it was as if it were trying to pull the gold from her father’s outstretched fingers.

“Meager,” the dragon said.

“It’s what was agreed,” her father said.

“What was agreed was meager.” But the dragon reached forward an open claw, and her father dropped the gold into it.

“Our deal has been witnessed,” her father said now. “Quarter payment has been made. The agreement is sealed.”

After a moment, the dragon nodded.

“You know where the farm is?”

The dragon nodded again.

“You’ll sleep in the fields you’re clearing,” her father said. “You’ll begin work in the morning.”

The dragon didn’t nod at this, merely smiled again, as if pondering how it had allowed itself to be so commanded.

“What?” her father said. “What is it?”

Another laughing rumble in the dragon’s chest, and it said, again, “Society.”

It took off into the air so suddenly Sarah and her father were nearly blown off their feet. Just like that, it was a shadow in the sky once more.

“It knows where the farm is?” she asked.

“It had to assess the work,” her father said, heading back to the truck.

“Where was I?” she said, following him. “You said you got it through Mr. Inagawa’s broker—”

“You don’t need to know everything.” He got behind the wheel and slammed his door shut.

She opened the passenger side door but didn’t get in. “You said I could drive.”

He let out that long breath through his nose again. “So I did.”

A moment later, they were on the road. Sarah shifted through the gears easily, even with the truck’s notoriously sticky clutch, even through the hills and turns that marked this part of the county. She avoided potholes, she signaled even though they hadn’t seen another car for miles, and she didn’t pump the accelerator the way she knew drove her father crazy. He had absolutely nothing to complain about. He complained anyway.

“Not so fast,” he said, as they trundled off the last stretch of paved street in Frome, Washington, the little hamlet their farm was in distant orbit of. “You never know when a deer could jump out at you.”

“There’s a dragon in the sky,” she said, looking up at the stars through the windshield. “The deer will be hiding.”

“If they know what’s good for them,” her father said, but at least he stopped talking about her driving. The road was black save for her headlights. No streetlights, no light

s from nearby houses as there weren’t any, just heavy forest closing in like the night itself. They drove in silence for a few moments, Sarah thinking about having to rise in six short hours to tend to the chickens and hogs before heading to school.

Then she remembered. “What was that about a witness? What was I a witness to?”

“Dragons think men lie,” her father said, offering an explanation but no apology, “and require at least one other to witness every legal agreement.”

“Couldn’t the witness just lie, too?”

“Of course, and of course it happens, but at the very least, the guilt spreads. Two men are compromised, not just one.” He shrugged. “Dragon philosophy.”

“We lied.”

He glanced over at her.

“We did,” she said. “We don’t have any gold to pay it with at the end.”

“I told you not to worry about that.”

“How can I? Dragons are dangerous. We lied to it. The guilt is spread between both of us.”

“There’s no guilt on you, Sarah.” His tone was such that no further questions were allowed, not least how much guilt he was carrying. “Besides, it’s more about compromising them. Their sense of what a word means. Their adherence to whatever they regard as principles.”

She couldn’t help herself: “That sounds a lot like what creatures with souls do.”

“Sarah,” her father warned.

The truck flew off the road.

At first, Sarah thought she’d somehow swerved into a ditch as the front of the truck dropped, slamming her into the steering wheel and sliding her father all the way off his seat into the dashboard. He called out, but more in surprise than pain, catching himself with his hand. Sarah slammed on the brakes, but nothing happened. They kept rocking forward as if they would turn a complete somersault—

Until they were rocked back, both of them helplessly thrown into their seats as the rear of the truck now dipped.

“What the hell?” her father said, alarmed.

The truck rocked forward again, and Sarah looked out at the road.

Pulling away beneath them.

“He picked us up,” her father said, stretching around to look out the back window.

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

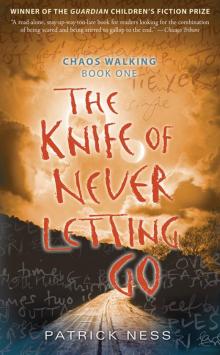

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

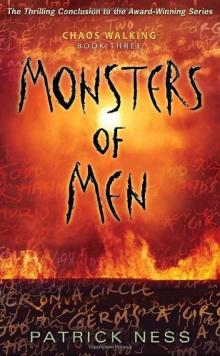

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

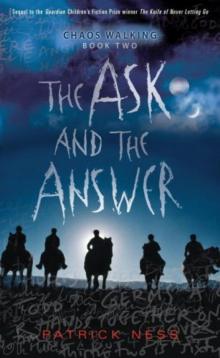

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

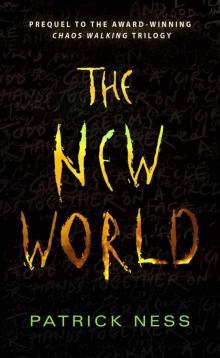

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking