- Home

- Patrick Ness

Burn Page 2

Burn Read online

Page 2

Sarah glanced, too, though she was too afraid to let go of the steering wheel to glance for long. The rear claws of the dragon had grabbed the truck on either side, like an eagle that had just caught a salmon. Sarah looked forward again, at the road and trees that were now rushing past beneath them as the dragon’s great wings beat, carrying them, she hoped, to their farm.

“He picked us up,” her father said again, barely controlling his anger, not seeming to notice the change back to he.

“Is he going to drop us?” Sarah asked.

She could see that her father didn’t know the answer. They were in the dragon’s claws. They had absolutely no say in what would happen next.

Two

HE HIT THE ground hard, catching his wrist, and spent a moment not moving, purely out of hope he hadn’t broken it. He breathed, and the pain settled down into an ache, not the livid sharpness of a break. He’d had those before, had the crooked collarbone to prove it. He gingerly rolled over and flexed the wrist. It hurt, but it would work.

With a grunt, he got to his feet. His bag had landed some twenty meters away and was only located after an increasingly frantic search. If he lost it, things would be much, much harder. Well, just say it: If he lost it, things would be impossible.

And that would be the end of everything.

There it was, though, deep in a fern that left dead spores stuck to his heavy winter coat as he dug it out. He unzipped the bag, checked the contents, closed it again. The important thing was there, but so were the rations of food and water that would allow him to make this journey interacting with as few people as possible.

Some interaction would be unavoidable. This didn’t frighten him.

He was prepared.

It was after midnight, but he had a long walk ahead and was keen to start. A clear sky and bright moon lit the way. He was at the edge of a forest, as expected, near a road that followed a river. He would mostly keep to the latter, but at this late hour, the road would work best to get the miles begun.

First, though, he knelt to pray. “Protect my path, Mitera Thea,” he said. “Keep me from distraction. Keep me from everything but the fulfilment of my goal.”

He did not pray for safe return. He did not expect one.

Prayers done, he stepped gently from the grass to the road, as if it might rise to bite him or give way underneath his rough shoe. Neither happened, and he turned south. He began to walk.

It was cold, but again, he was prepared. The coat over a woolen top, the thick woolen pants, gloves, and a cap that came down over his ears and nearly swallowed his face. It was a face others would trust, bright and surprisingly young, still a teenager, with blue eyes that neither threatened nor dazzled, a smile that was modest and appealing and wholly lacking in danger.

The last part was completely misleading.

He kept on through the night, the bag over his shoulders, enjoying the clouds of steam from his breath with an innocence that was perhaps younger than his apparent age. He passed a few houses, pulled far back from the road and isolated from one another, but he didn’t see a single car. In fact, it took until sunrise, when he was almost ready for his first rest, to hear the distant churn of an engine.

An enormous yellow Oldsmobile turned onto the road well ahead of him. Hiding was simple; he disappeared into the thicker forest on the non-river side of the road and waited. He sat against a tree, facing away from the road, listening to the car’s engine grow louder. He was unafraid. They would likely not have seen him, and even if they had, what more was he than a normal young man out walking? He dug into his bag for a small bite of hardtack biscuit while he waited for the car to be on its way.

He had the second bite halfway to his mouth before he realized the engine had stopped changing in pitch and volume. He listened. Yes. The engine was still running, but the car was no longer moving. He took a slow, slow peek around the trunk of the tree, back toward the road.

The car had stopped exactly where he’d entered the woods. It was enormous, all curved corners and obvious weight, like a bull ready to charge. It sat there in the frozen morning, on a deserted forest road, as if waiting for him. Through the trees he couldn’t quite tell how many people were inside or what they might be doing. There was a small click and the car seemed to settle. He guessed that this was as it shifted from drive to park.

He returned the biscuit to his bag and with a flick of his wrists, slid into his palms the razor-sharp blades hidden in his sleeves.

The woods were quiet at sunrise. Even without snow, the frost was thick. No insect yet buzzed, no morning bird sang. The only sound was the engine and his breath.

His eyes widened. His breath. Great steaming clouds of it, giving him away as surely as if he’d lit a fire. But then, he thought, why should this be a hiding place? Why should this be anything more than the curiosity of a random driver wondering why a man walked off the road into the woods? On the face of it, nothing unusual was happening.

He heard first one, then another car door open. Open but not close, the engine still running. The risk of another peek was staggeringly high, but how could he not? He held his breath, slunk down the tree until he was almost lying flat, then slowly, slowly, slowly, peered around the lower trunk.

The first gunshot took out the side flap of his hat and the middle of his left ear. The bullet reached him before the sound did and for a dizzying few seconds, he had trouble linking cause and effect, thinking he’d merely been stung by an out-of-season bee. The second gunshot tore away a fistful of tree terrifyingly close to his face. He dodged behind the trunk again as the shots kept coming, striking the trees around him, a shower of splinters raining across his body.

His ear hurt now, and when he touched it, his hand came away with an amount of blood that made him focus. He had no gun himself. There had been reasons, good ones, why he was only armed with knives and blades, plus it had been thought the level of counter-aggression he might face was too low to need his own gun.

Too late to complain, he supposed.

The firing stopped, and for a moment, the only sounds were the engine again and one angry, distant crow expressing its displeasure at being woken.

“There’s no way out of this, Malcolm,” a man’s voice called from the road.

Malcolm. One of the names he had been given to use from a list of a dozen, to cycle through should they be needed. It was a very early one, which probably meant something about who these men were, but he didn’t know what that was.

“Throw down your weapons,” the man continued. “Believe it or not, Malcolm, we want you out of this alive.”

“You shot me in the ear,” he called back.

“Throw down your weapons,” the man said again.

“I don’t have a gun.”

“Now that, I don’t believe.”

“Then we have a problem.”

“Not we, Malcolm,” the man said. “I don’t have any problem at all.”

Malcolm—he embraced the name for the moment—pulled his bag onto his chest, hoping it contained a surprise or two, knowing it didn’t. He heard a branch snap over to his right, almost certainly another man coming around to flank him. Another man with another gun.

The bag held nothing he didn’t expect. The only thing different about it from two minutes ago was the bloody handprint he’d added to the cloth.

“This cannot be,” he whispered. “This cannot be the end, so soon after the start.” He looked up into the rising gray of the morning. He put his hand back to his throbbing ear and whispered again, a plea, a prayer, a wish: “Mitera Thea, protect me.”

He held his breath and listened again. The walker to his right had either stopped or gotten better at disguising his steps. The man on the road was quiet now, was perhaps advancing, too.

There was a new sound. One the men wouldn’t have heard yet. But Malcolm did, because he had been listening for it.

“I surrender,” he called out.

A pause. “You do?” the man o

n the road said.

“If you give me a moment,” Malcolm said, “I’ll lay down my weapons and step away from them. No one needs to get hurt.”

“I agree with you, Malcolm,” the man said, “but how do I know you’ll keep your word?”

“I can only guess you know where I come from? What I Believe?”

“We have an idea, yes.”

“Then you know I cannot, will not lie to you. Even though you shot me, I’ll still surrender to you.” He turned his head so his voice would carry back better to the first man. “It’s a matter of principle.”

Malcolm could almost hear the man thinking.

The second man, clearly sensing the same thing, shouted, “It’s a trick!” to the first man, his voice contemptuous. “You know what these people are like. They’re fanatics. And the intel says—”

“Yes, I know what these people are like,” the first man said. “Which is why I know what they mean by that word. Principle.”

“As if there aren’t ways around principles,” said the second. “As if you and I don’t know how every principle and its opposite can be justified.”

“Are you philosophers?” Malcolm asked, genuinely curious.

For answer, a bullet struck the tree trunk above his head. “Philosophical question,” said the second man. “Was that a warning or was that a miss?”

“The philosophical part would be wondering if those were the same thing.”

“They’re not.”

“And there you are,” Malcolm said. “Your philosophy.”

“Will you shut up, Godwin?” the first man snapped.

Godwin shut up.

“I’m going to count to ten, Malcolm,” the first man said. “At ten, you’d better be standing where both of us can see you with your hands up. Understood?”

Malcolm closed his eyes and whispered a prayer of thanks, before saying, “Understood.”

“I mean it. One false move, and the philosophical questions will end. And that is a matter of my principle. Now . . . One.”

Malcolm breathed, pulling his senses away from his throbbing ear.

“Two.”

He exhaled through his mouth, watched the enormous cloud of steam that erupted from it.

“Three.”

Malcolm sat all the way up.

“Four.”

He pushed himself to his feet. He could see Godwin now, a stout man altogether different than Malcolm had expected.

“Five.”

“Quit staring at me and get a move on,” Godwin said.

“Six.”

“I’m sorry for this,” Malcolm said.

“Seven.”

“Sorry for what?” Godwin said, and exploded in a wash of fire and blood that Malcolm stepped back behind the tree to avoid, not incidentally stepping out of the line of sight of the first man’s gun. He still caught a wave of blood across the side of his face, Godwin’s mixing with his own and spattering Malcolm’s bag. Flames clawed at the tree trunk, scorching it but not catching.

The bag, of course, was fireproof.

“What the hell was that?” the first man shouted. “You said you’d surrender.”

“I am surrendering.” Malcolm pressed himself back into the tree trunk for what he knew was coming. “I can, however, be overruled.”

The screaming began a second later and ended two seconds after that, so at least the man did not suffer long. Malcolm waited until the roaring stopped, until the great lunging of wings quieted in the sky and all that was left was the tick of cooling metal and the pop of boiling rubber.

“Thank you,” he breathed, in unfeigned amazement. “Thank you.”

He gathered his bag, Godwin’s blood already drying. He didn’t look at the blackened circle of forest where Godwin had died, just headed quickly for the road.

The Oldsmobile was now a philosophical question all on its own: Was it still a car if most of it had ceased to exist and what was left fit into a shallow puddle? Was there a spirit to the Oldsmobile that could be said to still live if Malcolm remembered it?

He crossed the road ten meters down from it lest the heat in the tarmac melt his shoes. He entered the trees that led to the riverside, hoisted his bag onto his back, and continued his walk, not looking back.

He would rest later.

For now, there were a good hundred and eighty miles to go to the American border.

Three

“WHERE DID YOUR father find a blue?” Jason Inagawa asked Sarah as they walked the dirt road back from school.

“From the broker your father recommended,” Sarah replied, surprised.

The sun was out, but it was still near freezing. They kept their steps quick to stay warm; the school bus never seemed to make it out to the farms of the school’s only mixed-race girl and one of its very few Asians. Funny that.

“Yeah, but he never mentioned a blue,” Jason said. “I’ve never even heard of a blue around here before.”

“Me neither. But my dad said he was going to give your father a piece of his mind after what the dragon did.”

The dragon had not killed them. Of course. Dragons never did anymore. No one quite knew how long dragons lived—the rumors of immortality were surely just that—but a dragon valued its life enough not to break treaties hundreds of years old with a species that had proven especially adept at weapons of mass destruction. The periodic and costly dragon/human wars across the millennia had finally ended in the 1700s. Dragons had moved to their various Wastes around the world at more or less their own request, and a peace had endured long enough for humans to turn their aggression against themselves. World Wars I and II—from which the dragons had completely abstained—were the two most obvious examples, among countless smaller ones. Even just this week, the Soviet Union had captured an American pilot spying on them. Eisenhower had threatened retaliation if the spy wasn’t returned, but retaliation these days meant bombs big enough to vaporize entire cities. Sarah knew kids at school who prayed every night that they’d wake up in the morning. Truly, despite their ability to squash, swallow, or melt any human with barely an effort, dragons were quite far down the list of human worries these days.

This hadn’t made Sarah and her father’s flight home in their truck any less harrowing.

“If you ever pull a stunt like that again!” he had shouted, after the dragon had safely dropped them in their drive.

“You will do what?” the dragon rumbled. “Pay me even less?” It sounded amused and certainly didn’t look at all troubled by Gareth Dewhurst’s ranting.

“I mean it, claw,” her father said. “The authorities around here don’t take kindly to dragons.”

“The authorities cannot fly,” the dragon said, taking off, leaving her father mid-sentence and circling to the first field where it already knew it would work. Sarah watched it curl up at the edge of the trees. She had no way of knowing for sure, but some part of her felt certain that it had fallen promptly to sleep.

“I’m going to give Hisao Inagawa a piece of my mind,” her father had said, stomping into the house.

“People are always giving my father a piece of their mind,” Jason Inagawa said now. “You ever notice that?”

“They did to my mom, too,” Sarah said, feeling the usual quickening in her chest at speaking about her mother. “Especially when she caught Mr. Hainault cheating her at Frome Grocery.”

Jason left a respectful silence after this, as he had since she became motherless like him, a rarity in a time when it had mostly been fathers lost to war. It had brought them closer, but they’d been friends (and sometimes more than friends) since they were little kids who noticed they looked different from everybody else. They were only three weeks apart in age, both had even been born on their farms, though Jason’s first memories were all from “Camp Harmony,” the name given to the internment camp over at the Fairgrounds in Puyallup where all the Japanese families from Washington and Alaska had been forced to move. Even that had only been temporary: not-ev

en-yet-walking Jason Inagawa and his mother and father—both born in Tacoma, both U.S. citizens, both viewed as potential “enemy collaborators” by the government for no other reason than their heritage—had been sent on to a permanent camp in Minidoka, Idaho, where, two years into their three-year forced stay, Jason’s mother had died of pneumonia.

People talking about the Inagawas used the phrase “at least” a lot. At least Hisao had managed to get his own farm back; not everyone had been so lucky. At least no one bothered them too much anymore in this part of the country where there were at least a few other Japanese families around.

Sarah was careful to never say at least around Jason if she could help it. They also never went to the Puyallup Fair, which ran every September, no matter how many times people at school said it was great.

“Did the dragon tell you his name?” Jason asked now.

“I’m not even supposed to tell him mine. I’m not even supposed to call him him.”

Jason kicked a rock across the road as they walked. “The red we hired when I was a kid we called Grumpy. She didn’t seem to mind.”

“Like from Snow White? Ours would definitely mind.”

“You could call him Doc. Or Sneezy. That’s a good name for a dragon.”

“Or Lippy,” Sarah said. “He sure does know how to talk back.”

“They’re supposed to be scholars, blues. Super-smart, but tricky.”

Sarah scanned the horizon. “We should be able to see him now.”

They were coming around the last small hill that blocked the view of Sarah’s family farm—Jason’s was down the road another half-mile. The two fields that needed clearing were farthest off the road, edging onto the base of another hill with a radio tower on top that began the vast forest that reached all the way to Mount Rainier.

“There,” Sarah said.

The dragon rose from the field amid faint columns of white smoke, carefully controlling a stream of flame. He had to, lest he start a forest fire, but dragons could control their greatest weapon with terrifying ease.

“It’s small,” Jason said.

“Blues are smaller,” Sarah said, feeling oddly defensive about her dragon. Though, she supposed, it was in no way her dragon. “He’s still plenty big.”

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

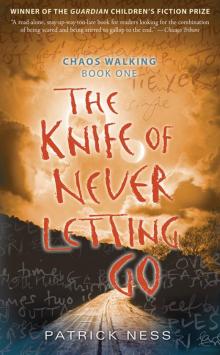

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

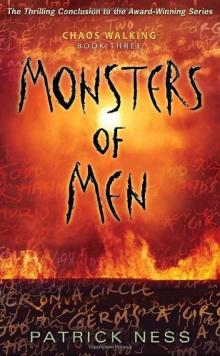

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

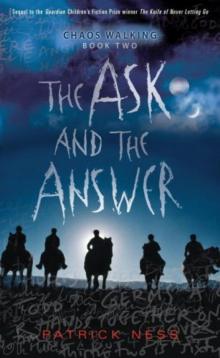

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

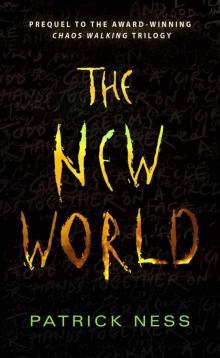

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking