- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Stone House Page 2

The Stone House Read online

Page 2

‘What do you think this is, Dead Poets Society?’ Miss Quill replies. ‘You’d like that, wouldn’t you. Do you think I’m going to lead you dancing through the underpass while you recite the underlying prames of the Renyalin series?’

‘Don’t you mean “primes”?’ April replies.

‘Don’t get her started on prames,’ Charlie whispers. ‘We’ll be here all day. They’re from our planet. The prames of the Renyalin change according to weather, time, and whoever is holding the aardvark.’

‘What?’ Ram says.

‘I’ll tell you later.’

‘Do I get an aardvark?’ Matteusz asks.

Charlie draws him a picture of an aardvark snorting ants through a rolled-up fiver.

‘You’re unusually quiet, Tanya,’ Miss Quill says. She folds her arms and stares at Tanya, eyes flicking back and forth between her features. She looks like an owl seeking out a worm.

‘I’m fine,’ Tanya replies.

‘If I’ve learned anything on this planet,’ Miss Quill says, ‘it’s that “I’m fine” means anything but.’

‘She’s fine, Miss Quill,’ April says. ‘Really.’ She adopts her bright, wide-eyed ‘how could you not believe me?’ face.

‘In that case, why are you all bothering me? Don’t you know it’s hot?’ Miss Quill says, fanning herself with the textbook.

SEVEN

STORM FRONT

After the last class, Ram is waiting for her at the entrance. ‘You’re late,’ he says. ‘If you’re going to make me come with you, then at least be on time.’

‘But you are coming with me?’ Tanya asks.

‘Only so I can report back that there’s nothing there.’

‘Your confidence in me is touching.’

Ram leans against the railings, watching people leave. ‘Do you never sweat?’ she says. ‘You look like you’ve fallen off the model conveyor. Stop it.’

‘I could try, I suppose,’ Ram says. Crinkling his brow only adds to the handsome.

‘Shut up,’ she says, leading them out of the grounds. They cross the road to the shady side of the street. If anything, the temperature has gone up. They weave through phalanxes of pushchairs and mums and dads complaining about how very ‘close’ it is, ‘yes, very muggy’, and that a ‘storm is coming, mark my words’. To be fair, the sky has got that yellow, bad-liver look that comes before a crashing thunderstorm.

Ram walks in front, swinging a tote bag. ‘What’s in the bag?’ Tanya asks.

Ram hands it over. ‘April made me take it.’

Tanya peers inside. There are two hand fans, two whistles, packets of biscuits, a torch, a compass, a portable charger, and two apples. ‘What do we need all this for?’

Ram shrugs. ‘She said, “You never know”.’

‘I do know that I won’t need a torch or a compass. Has she ever heard of apps?’

‘We’re lucky we got away with only this. She’s got far more in her bag. Says it’s better to be prepared than surprised.’

Tanya snorts. ‘Yeah? What would you rather have, a surprise party or a preparation party?’

‘April’s got a preparation party planned for her surprise birthday party. That’ll be fun,’ Ram says.

‘She’s already prepared for her surprise party?’

‘She’s prepared the most surprised surprise birthday party face you’ll ever see. She showed me. It’s like this.’ He raises his eyebrows as far as they can go, opens his mouth, eyes, and nostrils wide. ‘See? You’ve got to admit. That’s good. I know, I’ve been looking in the mirror.’

‘It’s alright,’ Tanya says. It’s more than alright but he doesn’t need to hear that.

‘She says that if she wasn’t prepared for it, she wouldn’t look nearly as surprised.’

‘That makes no sense whatsoever.’

‘It does in April Land.’

‘Are there rides at April Land? Wait. Don’t answer that,’ Tanya says as they enter the estate.

Kids belly flop over the swings, pushing with their feet, anything to get a breeze. That alien in an ice-cream van would make a killing here. An indifferent cat looks at her from the railings. It blinks once. Maybe it’s beginning to like her. It jumps down and pisses on a patch of dandelions. Maybe not.

‘It’s this way, isn’t it?’ Ram says, pointing down a narrow alley.

‘Have you been before?’ Tanya asks.

‘I went when I was a kid.’

‘What were you doing there?’

Ram stops walking, hands on his hips. ‘I know I said I’d come with you, but do we have to make small talk?’

‘Tell me the story and I’ll shut up,’ Tanya says. ‘Promise.’

‘Fine,’ he says, walking on. ‘Some mates dared me to jump over the railings and go in. Everyone said a mad old woman lived there who used to pull out kids’ teeth and make jewellery out of them.’

‘I’ve seen something similar at Spitalfields market,’ Tanya says. ‘So what happened?’

‘You said you’d shut up if I answered your question.’

‘I said when you’d told me the story.’

‘You really are a kid, aren’t you? Wanting your bedtime story.’ Ram sighs. ‘Fine. You want to know, I’ll tell you. Nothing much happened. I jumped over and had to wade through weeds to get to the front door. I was shorter then,’ he says.

‘Thanks for explaining how human growth works, Ram, it’s a subject so few know anything about.’

‘Right. Well, I reached my hand out for the door knocker and—’

‘Why do all creepy houses have door knockers?’ Tanya asks. ‘Couldn’t a few of them rig up a bell, just to make a change?’

‘Stop interrupting. Do you want me to tell the story or not?’

‘Sorry. No more interruptions. Carry on.’

‘Right, well, I knocked on the door and it went “thud, thud, thud”. Old-school horror. My mates were still on the other side of the gates, watching. I heard scuttling, close to the door. My heart was going for it, like I’d run from one goal line to the other. I didn’t run away, though.’ He is quiet then. They walk on. Tanya has to bite the side of her index finger to stop herself asking what happened.

‘Aren’t you going to ask what happened?’ Ram asks.

‘You’re infuriating,’ she says.

‘I think we both know that’s not true,’ he says.

She considers for a moment. ‘No,’ she says, ‘it really is.’

They stand on the street of the stone house. Their walking slows. ‘The door opened,’ Ram said, ‘at which point my mates legged it. I should’ve run as well, only there was something that made me want to go in.’

‘It felt like it was calling you?’ Tanya asks.

‘Exactly. So I stepped in. There’s a sort of hallway, more like another room. Really big. Staircase going up to an open landing. Furniture, or something I didn’t want to think about, covered in cloth. It was really dark, the windows so dirty that even without curtains it would’ve been impossible to see much. Cobwebs everywhere. I could tell though, that no one had opened the door. No one I could see anyway.’

The house is in sight. It looks even more isolated today. The grey of the stone house sits strangely against the blue sky and all the other houses seem as if they’re edging away from it.

‘Then what did you do?’ Tanya asks. She wants Ram to keep talking, anything to take away the weird, prickly feeling she gets whenever she looks at the house. It’s like a tickle from chilled bony fingers on her cheek, on her wrist, reaching through to the underside of her skin.

‘I walked further into the hallway and heard this scratching sound on the floorboards.’ He rakes his blunt nails against the railings. Paint peels off. ‘It sounded like something was coming towards me. At which point, I really did run. I vaulted the gate like a hurdles pro. My mates never brought it up again and neither did I.’

‘It was probably just a cat or something,’ Tanya says.

‘Yeah. A

really big cat with overgrown claws.’

‘Or something.’

‘So now what?’ Ram asks. ‘Which window?’

Tanya points up to the top window. It’s empty. Blank. The sash window looks like a hooded eye.

‘Well, she’s not up there,’ Ram says. ‘Case closed. Let’s go.’

‘Are you scared to go in?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ He opens the gate. It creaks wide. ‘We could do with a scythe,’ he says, trampling down the weeds in the garden.

‘You mean April didn’t have one in her Mary Poppins handbag?’ Tanya says.

‘Can we get on with this?’ he says, checking his watch. Tanya steps in front of him and knocks on the door.

The knocker is in the shape of a rose and really does land with a ‘thud’. She listens for scuttles or feet or anything at all. Nothing. No answer. Just the echo of the ‘thud’. She shakes the padlocks on the heavy door. ‘Don’t suppose you know how to pick a lock?’ she asks.

‘You’re the super brain. You figure it out.’

‘Fine. I will. There must be another way in,’ Tanya says. Brambles attach themselves to her clothes as she tries to get to the windows. They are all barred with iron and covered with ivy.

Ram moves away, picking his way through overgrown roses that have gone way beyond deadheading. He ducks down and under a bush, disappearing from sight.

‘What’re you doing?’ she asks. She can hear him rustling in unseen undergrowth and swearing. LOTS of swearing. He reappears a few minutes later.

‘There’s a back gate at the side. It’s pretty much covered with roses but we can climb over,’ he says. Now he looks sweaty.

Ten minutes later, they’re standing in the back garden, hoping that the dock leaves they’re wiping over nettle rashes are not more nettles in disguise. Old trees rise over them and there’s not one sliver of sun. In a day that could fry eggs on a belly button, Tanya and Ram feel like they’ve never been warm.

‘It must’ve been nice once. The garden,’ Tanya says, wading through the grass, avoiding the huge hole where a badger has scurried up a pile of earth. ‘It’s huge.’ She looks at a hedge growing out of a tub. It could’ve been elegant topiary. A squirrel, maybe. Now it looks like a woolly mammoth with its arse stuck in a bucket.

The stone house looks vulnerable from this view. Like when you’re sitting behind one of your friends and see they’ve left the label in their shirt and it’s not the size they say they are. Most of the windows at the back are broken, held together by webs. A conservatory leans against the house like a drunk friend at a party. Tiles have slipped from the roof and through the glass.

Something moves.

‘Up there. Second floor,’ Ram says, pointing up.

In the middle window of the middle storey, a girl places her palm against the window. Tanya can’t see much of her face other than her jaw opening wide and closing around a word. HELP.

‘Did you see that? She’s mouthing to us to help her,’ Tanya says, running to the conservatory and trying the door. It’s bolted shut but the glass is broken in every frame.

‘I’m not sure. She’s definitely there, though,’ Ram says, peering up, shielding his eyes against the bright sky.

‘Give me the bag,’ she yells to Ram. He hands it over. Emptying its contents out on the gravel, she wraps it around her hand and slams her fist into the cracked bottom pane.

‘Whoah,’ Ram says. ‘What are you doing? Call the police. Now.’

‘Like they’re going to take me seriously,’ Tanya says. She takes the glass out of the old dried putty, clearing the ground of any shards she finds.

Getting onto all fours, she begins to crawl through. On the other side, she stands up. It’s like a scene from Great Expectations, if Miss Havisham were a keen gardener. Plant pots and jam jars and barrels of all sizes are lined up around the outsides of the conservatory. Each of them once had a plant or flower growing inside, and each of them is completely covered in spiderwebs.

These aren’t just any old webs. They’re as thick as football socks. She touches a strand and it clings to her, holding on to her fingers and dragging a marigold with it. Tanya brushes it away, hoping she hasn’t shown how much it makes her skin creep.

A hammock is suspended in webs across one corner of the room, an ancient red velvet chaise longue lies at one end like a dried-out tongue; a table, wicker chairs around it as if waiting for three creepy bears, is laid out for afternoon tea. There are plates of desiccated scones and cake. A dead wasp lies in a jam tomb. Everything is covered with layers of dust, webs, and shattered glass.

‘Are you coming through?’ she calls to Ram.

‘Nope,’ Ram replies.

Tanya tries the handle on the door into the house. It’s locked. She tries to force it and, when that doesn’t work, shoves the door with her shoulder. That doesn’t work either. She takes a run at it. In films, people always bounce off the first time when they try this. Tanya doesn’t exactly bounce. She hits the door with a whack and all the breath goes out of her.

‘What are you doing?’ Ram asks.

Not answering, she tries again. It’s supposed to work on the second time, if not the third, but no. Her only reward is a slight cracking in the frame. The only other result is breathlessness and bruising. The fourth time, though, the cracking extends into a splintering that can be seen tearing through the wood. Plaster from above the door comes down like icing sugar.

A rushing wind blasts from inside the house. It sounds like it’s crashing through rooms and breaking everything in its way. Upstairs, she hears a scream.

‘We need to leave,’ Ram shouts. ‘Now.’

The wind builds into a crescendo, smashing through the windows, raining glass down through the glass roof. She crawls out, joining Ram, and they run, covering their heads, to the gate. Tanya pulls herself up and swings over the top, grabbing on to the ivy to lower herself, but it tears away in her hands. She falls to the ground.

Ram drops down next to her. They’re silent as they pick their way through the grabbing weeds of the front garden. When they’re outside the front gate, they look up at the house. The girl stands again in the top window.

EIGHT

VIEW FROM THE ATTIC

I scrape at the webs on the window every day. They stick to my fingers, but in time I make enough room to see outside. It’s gone dark suddenly. Thunder echoes across rooftops that go on and on. The sky is the dark yellow-blue of a bruise on the underside of my arm. The rest of London hides behind the trees. I read about this city, watched TV programmes set here, loved the music made here, and fought to reach it, but it doesn’t even know I’m here. No one else knows, either.

I last heard from Baba four months ago on WhatsApp. I then lost my phone to the Mediterranean Sea and by the time I got hold of another one and tried to call him, his number wasn’t recognised. He was ill, he said, that final time we talked. The crossing had been ‘difficult’, he said, which, in Baba’s language, means full of horror. He didn’t want us to go through what he had, he said, but once a rocket hit our house, we had to leave Syria, just as he had.

It’s been raining for hours. I hear it slam against the roof, upsetting the tiles. Last time I saw rain like this, I was in that small bedroom on my first night in London. It hit the window like tiny fists. In the room next door, another girl sobbed. Screamed for him to stop. The thunder did nothing to cover the sound.

I understand why people turn away from windows with girls in them. They look at our bodies and not our eyes. They don’t want to know. It was the same all the way through our journey. From the moment we left Damascus, my status changed. The smuggler didn’t look at us or ask our names as he bundled us into the car. My sister Yana and I were stuffed into the gap behind the front seats. Ummi lay on the backseat, covered, just as we were, with blankets and bags. I thought I could hardly breathe. In a few months I would find out what it was really like to not be able to breathe.

The scream

ing has started. It’s happening again. I’m not in the same room, but this house makes it play out time after time as if I were. The screaming next door turns to whimpering, her door slams. Slow footsteps to my door. Door key turns in the lock. The man who kidnapped me stands in the doorway, his hands on his hips.

My skin shrinks back to the bone.

I’m now trapped in a house filled with the journey’s nightmares and I cannot hear a call for prayer. I have to imagine that sound and hope I get the times right. I often pray that, insha’Allah, in one of the windows behind the trees, my baba is looking out, waiting for his lost family.

NINE

FACELESS ALICE

Ram appears on FaceTime. ‘What do you want now?’ he asks. He’s in his room, which is as immaculate as ever. Tanya angles her laptop so he can’t see the piles of clothes growing on her bed. On her floor. Everywhere apart from the wardrobe. There are more important things to think about than tidiness. Her mum disagrees.

‘So you believe me now, then?’ Tanya says. She can’t resist it.

Ram rolls his eyes.

‘I’ve been looking into the house,’ she says.

‘Yeah? And what have you found?’ he asks.

‘Deeds on the house going back years,’ she says, flicking through her notes. ‘It was bought by a property developer last year. He’s been given planning permission after a long wait and the property is due to be knocked down in a few weeks.’

‘Who owned it before?’

‘So you are interested then?’

‘Get on with it, would you?’

‘You know you said that people thought an old woman lived there?’

Ram nods. His eyes dart to the side then back.

‘Is someone with you?’ Tanya asks. Ram looks to his left. ‘April’s here.’

April’s head looms into view, close to the camera.

‘Hello,’ she says. Tanya can see right up her nostrils. April moves back and sits cross-legged next to Ram on his bed. ‘Sounds like you’ve found us a haunted house.’

‘I don’t think we’re going to find any ghosts,’ Tanya says.

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

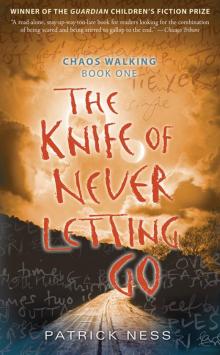

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

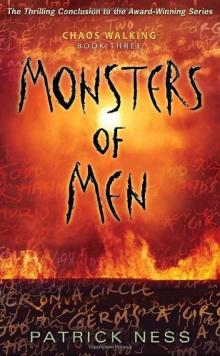

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

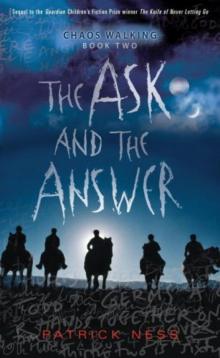

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

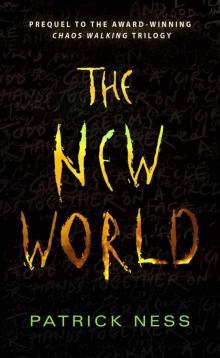

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking