- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Crane Wife Page 10

The Crane Wife Read online

Page 10

‘Ducks, ducks, ducks!’ JP said, throwing an entire slice of bread at a goose.

‘Little bits at a time, sweetheart,’ she said, bending down to show him. He watched her hands, almost panting with bread-anticipation.

‘Me!’ he said. ‘Me, me, me!’

She handed him the bits and he threw them all at the goose in a single motion. ‘Duck!’

She was lucky, she knew it, told herself so with annoying repetition. She’d found an affordable nursery near work that JP seemed to love and which was even mostly covered by Henri’s child support. Her mother could pick him up at the end of the nursery day if Amanda’s work overran and watch him until Amanda collected him on the way home. George, too, was always more than happy to take him in at odd times when needed.

And look at him. Christ, just look at him. Sometimes she loved him so much she wanted to eat him alive. Just put him between two slices of this stale duck bread and munch on his bones like a fairy-tale witch. The juice stain around his lips, the way he was brave about almost everything on earth except balloons, the way his French was so much more punctilious than his English. She loved him so much she’d tear the earth apart if anyone ever dared harm–

‘Okay,’ she whispered to herself, feeling the tears coming again. ‘Right then.’

She leaned forward and kissed the back of his head. He was a little bit stinky because bathtime was another chore running late today, but he was still purely him.

‘Mama?’ he asked, turning round, hands out for more bread.

She swallowed the tears. (What was wrong with her?) ‘Here you go, sweet cheeks,’ she said, handing him another batch. ‘This one, by the way, isn’t actually a duck.’

He turned back to the goose, amazed. ‘It’s not?’

‘It’s a goose.’

‘Like Suzy Goose!’

‘Yes, of course, I forgot we read that–’

‘She’s not white, though.’

‘There are lots of different kinds of geese.’

‘Is that different than goose?’

‘One goose, two geese.’

‘One moose, two meese.’

‘This one’s a Canada goose, I think.’

‘Canada moose,’ JP said. ‘What’s Canada?’

‘A big country by America.’

‘What do they do there?’

‘They chop down trees and eat their lunch and go to the lavatory.’

JP was thrilled at this news.

‘Is that a goose, too?’ he said, pointing.

She followed his finger to a great white bird wading through the pond. It had a splash of red feathers across its head and was looking carefully at the water between its feet, as if hunting.

‘I’m not sure,’ Amanda said. ‘A stork maybe?’

Then a thought occurred. A startling one.

But no, that had just been George’s dream, hadn’t it? She hadn’t believed that had actually happened. He hadn’t called it a stork either. He’d called it a crane, that was it. Did England even have cranes? She didn’t think so, but she’d certainly never seen a bird like this before. The size of it, for one thing–

JP coughed, and the bird glanced up at the noise. A bright golden eye, crazy like the eyes of all birds, caught hers briefly and held it for one second, two, before returning to its hunt.

Amanda felt briefly like she’d been judged. But then, she felt that most days.

‘Is Papa coming to feed the ducks with us?’ JP asked.

‘No, baby, Papa had to go back to France.’

‘Claudine,’ JP said, proud of his knowledge.

‘Indeed,’ Amanda said. ‘Claudine.’

JP looked back at the goose he’d been feeding. It had nibbled up the last of the bread and was poking its long neck at them in a request that managed to seem both embarrassed and assertive. JP just stood there, hands on his hips, foam Superman muscles bulging. ‘A goose,’ he said. ‘I am not a goose.’

‘No, you’re not.’

‘Sometimes I am a duck, Mama,’ he explained, ‘but I am not ever a goose. Not even once.’

‘Why do you suppose that is?’

‘If I was a goose, I would know my name. But when I am a goose, I don’t know my name, so I’m not a goose. I’m a duck.’

‘You’re a JP.’

‘I am a Jean-Pierre.’

‘That, too.’

He stuck his sticky hand in hers (how? How was it sticky? All he’d been handling was bread. Did little boys just ooze sticky resin, like snails?). Amanda glanced again at the stork/possibly crane thing, watching it until it disappeared behind the branches of an overhanging tree, still scanning the water for food.

‘Surely the fish are hibernating this time of year?’ she asked, then rolled her eyes at how stupid it sounded. She was becoming increasingly worried she was turning into one of those single mothers you saw on trains, speaking in a loud, clear voice to their child, as if pleading for somebody, anybody to please join in and give her something else to talk about besides goddamn wriggling.

‘What’s hyperflating?’ JP asked.

‘Hibernating. Means sleeping off the winter.’

‘Oh, I do that. I get into bed and I sleep the whole winter. And sometimes, Mama? Sometimes, I am winter. Je suis l’hiver.’

‘Oui, little dude. Mais oui.’

By the time she’d got JP to bed that night, she found she was so tired she couldn’t be bothered to even make lunch for the next day. She was supposed to have time off in lieu for all these idiotic Saturdays out in soul-sapping middle-of-Essex nowhere, but Head of Personnel Felicity Hartford had made it clear that ‘time off in lieu’ was like the gold standard: worth the world, as long as no one ever asked to spend it.

She called George that evening instead, and they talked about Kumiko – who Amanda still hadn’t met; it had got to the point where it seemed George was purposely keeping her secret – and about the astonishing amount of money he and Kumiko were suddenly being offered for the art they made together, a development Amanda instinctively mistrusted, like telling everyone you’d won the lottery before doing the final verification of your numbers.

‘You remember that bird you said you saved?’ she asked. ‘What was it? A stork?’

‘A crane,’ he said. ‘At least I’m pretty sure it was a crane.’

‘Did that really happen? Or did you just dream it?’

He sighed, and to her surprise, there was a real annoyance in it. She pressed on quickly. ‘Only I think I may have seen it today. At the park with JP. Tall white thing, hunting for fish.’

‘Really? That park near your flat?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Gosh, wouldn’t that be something? Gosh. It wasn’t a dream, no, but it sure felt that way. Gosh.’

She talked to her mother next, mostly about her father. ‘Well, almost none of that makes sense, dear,’ her mother said about Kumiko and the art and the money and the crane. ‘Are you sure?’

‘He seems happy.’

‘He always seems happy. Doesn’t mean he is.’

‘Don’t tell me you still worry about him, Mum.’

‘To meet George once is to worry about him forever.’

Just before she lay down in bed to pretend to read, Amanda picked up her mobile again and clicked ‘Recents’. Henri was third down, after her father and her mother. She hadn’t spoken to anyone else the entire weekend. She thought of calling Henri to see if he’d made it home safely, but that, of course, was impossible, for so many reasons. And what would she say? What would he say?

She put the phone back down and turned off the light.

She slept. And dreamt of volcanoes.

Work on Monday morning involved an analysis of the data she’d collected at the weekends – numbers of cars, how long each had waited on average, possible alternate traffic signalling or routing or directional changes that might help. She never tried to explain this part of her job to others, not after seeing how their faces stretched back

in terror that she might keep talking about it.

But, well, people were dumb, and she found the job interesting. The sorting out of traffic may not have been all that dynamic, but the solving of a problem could be. And these were problems she could solve, was even developing a certain flair for solving, even possibly so well she may have been shifting Felicity Hartford from anonymous loathing of her into reluctantly approving awareness.

Though Rachel – who was, after all, her immediate superior – was starting to prove a real obstacle.

‘Have you finished the analysis yet?’ Rachel asked, standing at the end of Amanda’s desk reading a report, as if Amanda’s work was too boring for eye contact.

‘It’s 9.42,’ Amanda said. ‘I’ve only been here forty-five minutes.’

‘Thirty-one minutes?’ Rachel said. ‘Don’t think your tardiness hasn’t been noticed?’

‘I worked all day Saturday.’

‘Queue counts should only take the morning? I hardly think that’s all day?’

It had been like this since the picnic. Nothing obvious had changed, no big gestures or declaration of eternal enmity, just the slow withdrawal of lunch invites, an increased brusqueness to work requests, a general chilling of atmosphere. Refusing to look at her was new, though. They must have entered a new phase, Amanda thought. All righty then.

‘How’s it going with Jake Gyllenhaal’s brother?’ she asked, turning back to her screen. Out of the corner of her eye, she at least saw Rachel look up.

‘Who?’

‘The boy from the park,’ Amanda said, faux-innocently. ‘The one who threw olive oil all over you.’

‘Wally is fine?’ Rachel said, a little frown (plus, Amanda was thrilled to see, a little frown line) briefly scarring her immaculate face.

‘He’s called Wally?’ Amanda said, for what was the third or maybe fourth time. ‘Who’s called Wally these days?’

‘It’s a perfectly normal name?’ Rachel said. ‘Unlike certain other names I could mention? I mean, Kumiko for someone not even Japanese?’

Amanda blinked. ‘What a weird thing to remember. And how do you know she’s not Japanese?’

‘Not really weird?’ Rachel said. ‘You talk about it, like, incessantly? Like you have no life of your own so you’ve got to live through your father’s? It’s sad? Is what it is?’

‘Sometimes, Rachel, I don’t know how you think–’

‘The report, Amanda?’ Rachel said, green eyes flashing.

Amanda gave up. ‘By lunchtime,’ she said, then put on a huge fake smile. ‘And hey, maybe we can have a bite and go over it together. What do you say?’

Rachel made a fake disappointed sound. ‘That would have been super? But I’ve already got plans? Just on my desk by one?’

She walked away without waiting for Amanda’s response. We could have been friends, Amanda thought.

‘And yet somehow, no,’ she said to herself.

‘Out of the way, fat ass!’

The cyclist’s elbow sent Amanda’s coffee flying towards a pavement heaving with City workers on their lunch breaks, including a businesswoman who’d picked the wrong day to wear cream. The cup hit the pavement at the woman’s feet, splattering her with a wave that reached all the way to mid-thigh.

The woman stared at Amanda, mouth agape. Amanda, torn between the embarrassment of having so many people hearing her called ‘fat ass’ and the embarrassment of having practically thrown coffee at an innocent bystander, tried to seize the initiative.

‘Fucking cyclists,’ she said, feeling the sentiment truly but also hoping the woman would follow her on the shift of blame.

‘You’re standing in the bike lane,’ the woman said. ‘What did you expect him to do?’

‘I expected him to give way to a pedestrian!’

‘Maybe your ass was too fat for him to avoid.’

‘Oh, fuck you,’ Amanda said, giving up and walking away. ‘Who wears cream in January anyway?’

‘You’re paying to clean this!’ the woman said, stomping after her.

Amanda tried to push her way through all the suits, male and female, that had slowed to watch the altercation. ‘What are you going to do?’ she said. ‘Have me arrested for dry-cleaning?’

A handsome Indian businessman stepped solemnly in front of Amanda. ‘I really think you should offer to pay for the woman’s cleaning,’ he said, in a thick Scouse accent. ‘It’s the proper thing to do, like.’

‘Yeah,’ said a second handsome man. ‘It was your fault, after all.’

‘It was the cyclist’s fault,’ Amanda said. ‘He knocked into me, and now he’s miles away, no doubt cresting the wave of his own self-righteousness.’

The cream-wearing woman caught up and grabbed her by the shoulder. ‘Look at me!’ she said. ‘You’re going to pay for these.’

‘Don’t worry,’ said the handsome Indian Scouser. ‘She will.’

Amanda opened her mouth to fight. She was even ready, she found to her surprise, to physically threaten this woman in some way, ready maybe even to follow through on an actual slap (even an actual punch) if the woman didn’t take her goddamn hand off Amanda’s shoulder. Amanda was tall enough and big enough not to be messed with and by God people should just go ahead and learn–

But when she opened her mouth to start, she found herself, once again, overflowing with tears.

Everyone was looking at her, their faces angry that she’d brought injustice into their day, waiting firmly to see it righted. She tried to speak again, tried to explain in no uncertain terms what the woman could do with her cream trousers, but all that came out was a choked sob.

‘Seriously,’ she whispered to herself, ‘what is wrong with me?’

Moments later, though they seemed like hours, Amanda had exchanged business cards with the woman, under the disdainfully triumphant eyes of the two handsome men. She left them to whatever high-finance ménage à trois they’d end up with and took the rest of her lunch to a small green-space near the office, only realising as she sat down on the one remaining open half of a bench that she now no longer had a coffee to go with it.

They’re angry tears, she told herself as she cried into her cress sandwich, made in a hurry this morning without mayonnaise because she was late for JP’s nursery. They’re angry tears.

Henri was right, though. Not very different shadings.

‘Are you all right?’ said a voice.

It was the woman sitting on the other half of the bench, a woman Amanda had barely registered as she sat down, a woman also, bafflingly, wearing cream. Seriously, it was fucking January, people.

But this time, at least, it was a cream outfit embracing a kind face, yet one that had (Amanda was surprised to find herself thinking) also seen the world, and had returned knowing maybe not so much about the world but more about herself than Amanda could learn in a lifetime.

‘Long day,’ Amanda coughed out, confused. She turned back to her sandwich.

‘Ah,’ said the woman. ‘Myths tell us the world was created in a day, and we scoff and we call them metaphors and allegories, but on a day like today it seems as if we could break our backs the whole morning to make the universe and someone would still ask us to come to meetings in the afternoon.’

Amanda smiled back politely, feeling the first inklings of alarm that she’d sat next to a mad person. But then again, no. This odd little woman seemed, somehow, to have understood and was merely saying so. In an odd way, yes, but one that was also oddly comforting.

I keep saying ‘odd’, Amanda thought. The woman’s accent was also oddly (‘and again’) unplaceable, clear but foreign in a way that suggested not a country but a kind of ancientness. Amanda shook her head. No, she thought, she’s probably just Middle Eastern. Or something.

‘I am sorry,’ the woman said, three words, not the usual contraction, but even then it wasn’t an ‘I am sorry’ that meant ‘I’m sorry’. It was an ‘I am sorry’ that meant ‘Excuse me’.

Amand

a looked back over.

‘This seems scarcely credible,’ the woman said, ‘but is it at all possible that you are Amanda Duncan?’

Amanda froze mid-chew.

‘I am sorry,’ the woman said again, and this time it meant ‘I’m sorry’. ‘This is quite amazing, is it not?’ she said. ‘We have not met, but I feel as if we have.’

Amanda sat up straighter, astonished. ‘Kumiko?’

For all of a sudden, it could only be her.

A cyclist – possibly the same one from earlier for all Amanda knew, they all looked identical, with their crotch-fitting tights and their air of ethical entitlement – raced past, perilously close to the bench, causing them both to rear back. Amanda’s cress sandwich tumbled to the pavement, lying there like a murder victim.

‘Fucking cyclists!’ she screamed after him. ‘Think they own the world! Think they can do whatever they like! Complain you’re in their way even when you’re on a FUCKING PARK BENCH!’

Amanda sat back, lunchless, drinkless, furious that the tears were coming again, furious that everything felt like it was sliding apart, that it was doing so for no good reason, that nothing had changed except something slight, something she couldn’t put her finger on, something that took everything that was her life and placed it slightly higher up on a mountainside so she had to climb for it, and when she got there, there was only more mountain, there was only ever going to be more mountain for as long as she lived, and if that was the case then what was the goddamn point? Of any of it?

A handful of tissues nudged gently under her nose. Unnerved by where that chain of thoughts had run from and how quickly it had reached its alarming destination, Amanda took the tissues from the woman, from Kumiko it now seemed impossibly to be, and wiped away her tears.

‘I know,’ Kumiko said. ‘I hate them, too.’

It took Amanda a moment to realise what Kumiko meant. When she did, she looked up in wonder and burst into fresh tears.

Which at least weren’t angry.

‘Duncan Printing?’

‘Is that the famous artist George Duncan?’

‘. . .’

‘That’s him, isn’t it?’

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

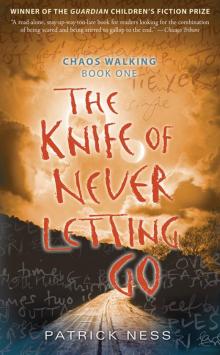

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

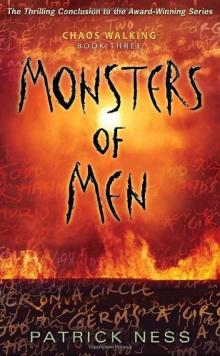

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

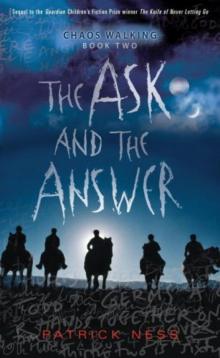

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

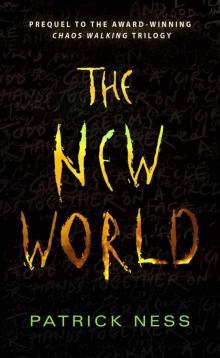

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking