- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Stone House Page 13

The Stone House Read online

Page 13

‘You’re not going to tell me, are you?’ he says.

‘I don’t usually promote ignorance but in this case I think it best.’

‘I have absolutely no idea how to take that,’ Alan says, driving off. There’s much more traffic now.

‘Where would you like me to drop you?’ he asks. ‘I can go anywhere you like.’

‘I would’ve thought that was obvious,’ she says.

‘Not the—’

‘Yes, the.’

‘But I thought you’re not supposed to go there? Isn’t there an injunction?’

‘They say that, but has it actually gone through yet? I suspect not. And anyway, there are lots of things I’m supposed to do but don’t. I don’t eat green things, they taste of weeds; take vitamins, don’t trust anything in capsules; wash, overrated nonsense.’

‘Right,’ he says, nodding.

‘I was joking about the last one,’ she says.

‘Of course,’ he says. ‘I knew that.’

‘Although I never wash clothes.’

‘That’s another joke, isn’t it?’ Alan says, looking hopeful.

‘Alan, you’re going to be absolutely fine,’ she says. ‘Now drive this dirt-coloured cube faster. Tanya’s in trouble.’

THIRTY-EIGHT

THE DOOR

CRAAAAAAAAAK. Tanya wakes up and fumbles for the torch, pointing it towards the door. It’s opening. Very, very slowly. She leans up to the other bed and grabs Amira’s arm. ‘Amira,’ she says, ‘Wake up. It’s letting us out.’

Amira leaps back as if she’s been burnt.

‘Sorry.’ Tanya knows that’s not how you treat someone with trauma, but they have to move. Now. ‘I need you to come with me. It might be playing with us and decide to change its mind. COME ON,’ she shouts.

Amira stumbles out of bed. She’s wearing a long, old nightdress and, with her hair over her face and a lantern in her hand, looks more like a ghost than anything Tanya’s seen in the house so far.

Tanya runs for the door and, throwing her weight at it, pins it to the wall until Amira joins her. She’s not going to let it keep them prisoner again. Amira takes her hand. They hurry along the corridor. Ahead, the girls who used to laugh at Tanya stand with hands on their hips.

‘You really need to sort out your hair, Tanya,’ one of them says. ‘We’re not being funny or anything, just giving you advice. It doesn’t suit you.’

‘She doesn’t need your advice,’ Amira says, barging through them, shielding Tanya.

‘Cow,’ the blonde one says as they pass. She spits at Tanya’s face.

At the top of the stairs, a man tries to grab Amira’s hand. Tanya swats it away. A woman cajoles from the corner, calling Amira, ‘A beauty. A real beauty. Let me put some lipstick on you.’ They try to squeeze their way through a crowd of people boxed into the hall, all on tiptoe, lifting their heads as high as they can to breathe. In her peripheral vision, Tanya sees boats bobbing and people screaming, looking over the sides, reaching down. Amira cries out. It sounds like her heart is ripping.

‘Leave her alone,’ Tanya shouts. She doesn’t know how she’s not falling over. She can barely see anything except for bullies, boats, and someone she fancies turning around and around on the spot but never seeing her, like they’re stuck in a haunting game of blindman’s bluff.

She misses a step on the stairs and Amira steadies her. If they weren’t propping each other up, they’d both be facedown at the foot of the staircase.

When they get into the hallway, the house goes quiet. No one’s chasing them. Tanya’s heart keeps beating overtime in case they have to run. They are, suddenly, the only ones there. There’s no storm shaking the house. No nightmare people.

The quiet is worse. The house is waiting, watching. It feels like an itch under the skin.

Tanya tries the handle on the front door. ‘Of course,’ she says. ‘Locked.’

‘Maybe your friends locked it after they left with the police?’ Amira says, hope woven through her voice.

‘Maybe,’ Tanya says, ‘but I don’t think they did this.’ She points to the web knitting itself across the door. They’re being sewn in from the inside. ‘Could you go and check the back door?’

‘It’ll be the same. Any access point gets covered over. It’s what the house does whenever I try to leave,’ Amira says. ‘I’ve stopped trying. It just makes it harder to see outside.’

Tanya goes to check. Amira’s right. The back door is choked with spun silk. Cobwebs extend across the glass of the conservatory so that it looks like a giant dreamcatcher. That’s exactly what the house is: the dreamcatcher of Shoreditch, where dreams are plucked out of people’s heads and preserved. The house is being mummified from the inside.

She pulls at a section of web. It stretches in her grip and other strands join it, wrapping round her hand like a boxer being bandaged for a fight. ‘OK,’ she says to the house. ‘Stop, please. I won’t try to get out.’

The section of web slackens and falls, slithering across the floor.

As she walks back through the room of dolls, one of them falls from the shelf. Then another. She runs out before she’s caught in a mass suicide of moulded figures in national dress.

When she returns to the hall, Amira is crouching down, tracing the scratched lines on the floor with her fingers. ‘I wish I understood what this was,’ she says. ‘They might tell us what to do. Like a spell.’

‘You think this is some kind of magic?’ Tanya says.

‘You don’t?’

‘There was a rumour that the old woman who lived here was a witch, but that means nothing.’

‘It could mean something. What if you’re overlooking a something that could help?’ Amira says.

‘Women who live differently have always been called witches,’ Tanya says. She kneels and brushes her hand over the scratches. ‘This is probably where furniture has been dragged out to be sold. Most of the rooms are empty and they wouldn’t care about keeping a floor polished when it’s about to be demolished.’

‘I’m trying to help,’ Amira says.

‘I know. I’m sorry. Have you seen anything that could’ve caused it?’

‘No, although if there is something, it is probably concealing itself, just as it can hide us.’ Amira walks all the way around the markings. ‘I’ve looked at it from the landing and from down here. Close up, it looks like lots of very fine scratches with no overall pattern, but from the first-floor landing, when there’s enough light, it looks like lots of circles.’

Tanya runs up the stairs. She looks down at the hallway floor. She can see what Amira means. There are shadows cast across the floor, but she can see how there’s cohesion and geometry to the etching. From up here it’s a series of perfect circles.

Behind her, she hears footsteps. A man walks towards her from the end of the corridor and unlocks the door to one of the bedrooms. As he goes in, something crashes down. Seconds later, the same man is at the end of the corridor again. He walks to the bedroom and unlocks it, disappears inside. Another crashing sound. Seconds later, he’s back at the far end of the corridor.

‘He’s there, isn’t he?’ Amira calls up, her voice shaking.

‘He can’t hurt you,’ Tanya says.

The man walks towards her, unlocks the bedroom. Amira retreats into a corner of the hallway and sits on one of the sleeping bags, her knees tucked to her chest.

‘Do you enjoy this?’ Tanya shouts. ‘I’m talking to you, house. What have you got to say for yourself?’

‘Don’t make it angry,’ Amira whispers. ‘The nightmares get worse.’

‘Come on, then, house,’ Tanya yells, ‘what else can you do? Are you repeating things over and over to send us mad? Do you think we’re going to crack? What will you do then, prop us in a corner like mannequins? Have us sit in the conservatory taking tea for infinity? Make yourself a house of bones?’

Something taps on the walls. Tap, tap. Tap, tap, tap.

‘Y

ou don’t like it when people fight back, do you?’ She walks down the stairs, calling out. ‘You’re a coward. I think your defence mechanism is to show people their fears so that they run away. Only we want to leave and you won’t let us. Your defence has become an attack.’

TAP. TAP. TAP TAP TAP.

The sound gets louder. It seems to be coming from underneath the floorboards. Something is coming. Scuttling.

Tanya comes to a stop next to Amira. The cobwebs are creeping up Amira’s back.

Tanya stamps them down. ‘Just piss off, would you?’

‘Stop it, Tanya,’ Amira says. She stands up. ‘Please.’ She pulls at Tanya and makes her face her full-on.

‘I can’t,’ Tanya says. ‘I’m not going to give up like you have. I’m sorry, but you need to fight.’

‘You know NOTHING about fighting,’ Amira says. Her teeth are bared, her eyes wide. ‘You don’t know what it’s like to put everything into surviving, only for the person who keeps you going to drown in front of you. Your dad died, and that’s horrible, but I left my home when war destroyed my town, crossed Europe, lost my whole family. I’ve been jeered at, insulted, assaulted, and only just escaped. That is not an unusual story for people, I know. I got here. I know how to fight, Tanya, better than you, better than most.’

Silence. The tapping has stopped.

Very light footsteps come from the end of the hall, too far away for torchlight. The footsteps are coming their way. The owner of them steps into the light.

‘No,’ Amira says, so quietly Tanya almost doesn’t hear. It’s a girl, younger than Amira, but who looks just like her.

‘Amira?’ the girl says. ‘It’s Yana.’ Yana reaches out. ‘Will you play with me, Amira? Will you play?’

Outside, a dog barks. Someone is coming down the path. Probably the police again, searching for Tanya.

Amira looks up and moves towards Yana.

A key scrapes in the lock as if it doesn’t quite fit. Tanya makes out some muttering. ‘We need to hide,’ she says, tugging on Amira’s clothes.

‘No. Yana might leave,’ Amira says. ‘I haven’t seen her this close up since . . .’

Yana smiles and holds out her hand. Amira mirrors her, stretching out hers.

‘Don’t,’ says Tanya. Turning her own sister to dust would crush Amira.

Amira and her sister touch very briefly then Yana begins to fade. The rest of the house can be seen through her.

‘The house is losing concentration,’ Amira says, trying to hold Yana’s hand but it now passes through. She’s crying silently.

‘It knows someone’s trying to get in,’ Tanya says. Cobwebs twist into the keyhole.

The door won’t open more than a few centimetres. It’s webbed shut. A penknife appears at the top of the frame, sawing down.

With what sounds like a swift kick, the door opens. Miss Quill slips through. She’s alone. She turns on the torch, straight in Tanya’s face.

Tanya turns away, dazzled. ‘Thanks for that, Miss Quill,’ she says. She doesn’t know whether to hug Miss Quill or swear at her. She often feels like that.

‘She can’t hear you,’ Amira says. ‘Or see you when you’re in the web. You need to brush it off, remember?’

‘What about you?’

‘She’s looking for you, not me. I’ll only make things more confusing. Quickly,’ Amira says.

Tanya briskly strokes the air above her goosebumped arms. Nothing happens.

Miss Quill walks towards the stairs. ‘Tanya?’ she hiss-whispers, looking up to the second floor.

‘I’m here!’ Tanya shouts.

‘Keep going,’ Amira says. ‘I’ll do your back.’ Tanya’s shoulders tingle as Amira brushes away the connected silk.

Tanya waves her hand back and forth on any spot above her forearm where she feels the faint resistance of web. In the small amount of light, she can just about see a thin skein of silver float away. It’s like rubbing at a lottery card. Miss Quill’s torch whips back through the dark, shining at Tanya.

‘I hope your arm is joined to the rest of you, Miss Adeola,’ Miss Quill says as drily as if the arm had turned up late for class all by itself and waved from a desk. ‘Otherwise I’ll have to turn your disembodied limb to dust and that would be tiresome.’

Tanya smooths off the rest of the web. It’s tiring. She’s not taking up exfoliation if this is what it’s like. She needs energy for other things.

‘There you are,’ Miss Quill says. She could sound a bit more pleased to see her. She’s been imprisoned by a sociopathic building all night, that should get her some Quill love, but no, not even a comradely chuck to the chin. ‘That was easier than I expected. We need to leave. Now. Before it becomes harder than I expected.’

‘In a minute. I need to wait for Amira,’ Tanya says.

Miss Quill’s eyebrows twitch. ‘You found her?’

‘She’s over there,’ Tanya says, pointing to where Amira was sloughing off her own shroudlike covering. Only the slight widening of Miss Quill’s eyes shows any surprise at Amira being revealed. It would make an amazing illusion. She wonders if any magicians use it. Get Derren Brown on the phone.

‘If you could hurry up and make your lower half visible, Amira? It may cause Neighbourhood Watch some consternation if they see you floating down the road,’ Miss Quill says.

‘Neighbourhood Watch weren’t much good when she was trapped here,’ Tanya says.

‘There’s no time to be indignant, Tanya. Mr Oliver intends to start knocking the house down today. I do not want a wrecking ball to the face, thank you.’

Just as Amira’s ready, the scuttling starts. And the tapping. TAP TAP TAP. And a new sound, a soft shushing along the floor.

Ivy is emerging from the faded wallpaper and weaving towards them along the floor.

Miss Quill grabs them both by the shoulders, propelling them towards the door. ‘RUN.’

A band of ivy tendril loops around Tanya, pressing hard into her stomach. Her wrists are cuffed together with tendrils. The ivy is snaking around Amira, too.

‘Miss Quill!’ Tanya shouts. She gasps as the ivy tightens, breath forced out of her lungs as it drags both her and Amira towards the wall.

Miss Quill runs after them, tearing at the ivy around Tanya, but it makes the ivy tighten more. She scrapes her penknife against the plant, but it doesn’t even spill sap. She stabs it and twists.

Miss Quill is lifted off her feet, thrown backwards by a force they can’t see. Her arms grip the frame on either side of the dining room, but she can’t hold on. Her back arches. She can’t hold on any more and flies through, landing hard against the wall. She slumps to the floor, head on one side. She looks like a doll in business dress.

‘Miss Quill!’ Tanya calls out. ‘Can you hear me?’

Miss Quill doesn’t move or reply. The door to the dining room slams shut. They’re on their own, again.

THIRTY-NINE

BACK TO THE OLD HOUSE

Tanya and Amira huddle together, wrapped in ivy, cobwebs regathering around them.

Outside, a truck bleeps its reversing song. Cars arrive. The chatter of builders.

‘They won’t be able to see us,’ Tanya says. ‘They’re coming to pull down the house and we’ll look like part of the walls.’

‘We’ve got to get out,’ Amira says. ‘There must be a way.’

‘You!’ Tanya says, remembering. ‘You saved me last time.’

‘Last time you were held captive by ivy?’ Amira says, voice full of disbelief.

‘In my dream. I did everything I could to wake up and I was held just like this, hands behind my back, against the wall.’

The demolition team comes through the door, laughing, holding tea, sledgehammers, and machinery that looks like it’d be good for destroying a house made of stone. It’d look like a fun job if she weren’t imagining them blithely swinging the hammer at her head.

‘Help!’ Tanya cries out.

‘They won’t be able t

o hear you, I’ve told you,’ Amira says. ‘How did I do it in your dream?’

‘You just spoke to me and I woke up.’

‘I’m speaking to you now. That doesn’t seem to be working,’ Amira says.

‘You’re getting facetious, you know,’ Tanya says. ‘I like it.’

‘You bring it out in me. My sister did as well.’

‘Wait,’ Tanya says. ‘That’s it.’

‘What?’

‘You saw your sister just now. She faded away, but you were able to touch hands, really briefly.’

‘I’ve never been able to do that before,’ Amira says, ‘I’ve never been close enough—she’s always a corridor away.’

‘And everything else you’ve touched, the nightmares, they turn to dust if you touch them.’

Amira nods. ‘It’s why there are piles of dust everywhere: I’ve got a lot of nightmares. How does that help?’ she asks.

A radio is switched on in the corner. Tea is drained. Some of the men go upstairs. Work’s about to start. One of them slams a hammer into the wooden railing on the landing. Spindles fall.

‘Careful,’ one of them says, ‘I’ve got to go up there. Oliver said there might be valuable stuff left. Not that I’ll hand it over, he’s not paying enough. This place gives me the willies. I don’t fancy being left upstairs without a staircase. You can smash it as much as you like after.’

The ivy shivers around them. The house is watching the unbuilders, waiting, worrying.

‘I’ve got a hypothesis,’ Tanya tries to say. A tendril has encircled her neck and is squeezing breath and words out of her. She twists her hands in their ivy handcuffs. They’ve loosened, as she’d hoped. The house must be distracted again.

She can move her fingers just enough to reach part of the plant. The ivy recoils and contracts, pulling her against the wall for one moment, then turns to dust.

The workers look over at the big mound of dust on the floor, with two people-shaped dips in it.

‘You see that, Danny?’ one of them asks.

Danny nods, mouth open.

‘Told you this house was weird.’

Danny nods again and looks around the house.

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

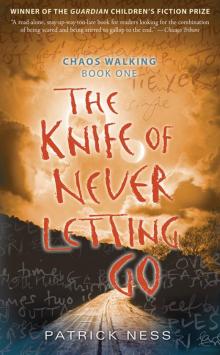

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

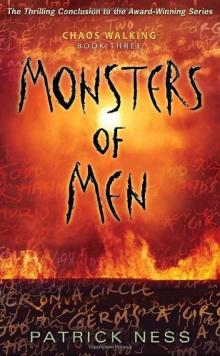

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

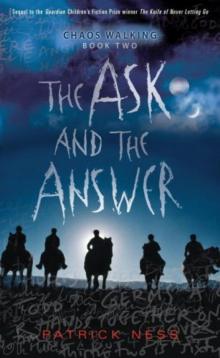

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

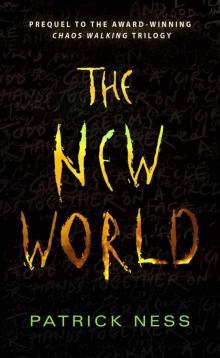

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking