- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Stone House Page 15

The Stone House Read online

Page 15

The spider’s legs click together. Tanya’s mum, a floating molasses cake, her dad smiling, Tanya being buried in her father’s grave. Each image lingers then fades.

‘It’s spinning dreams like a web,’ Tanya says. ‘I don’t think it knows the difference between good dreams and nightmares.’

As it weaves the dreams, it looks around the room and other images appear. Corridors and screams and—

‘That is quite enough, thank you,’ Miss Quill says to the spider.

‘In its dream, it showed its baby climbing into a coffin. What if it was Alice’s? She died last year,’ Tanya says, running towards the stairs. ‘We have to find out where she was buried. I found a load of papers in the attic. Something up there could help.’

Halfway up the stairs, she looks down at them all staring up at her. ‘Well, come on then. There are a LOT of documents to get through. Oh, and be careful walking across the landing. Someone broke the railing.’

FORTY-FOUR

THE PAPERS

Tanya looks down from the attic. Miss Quill, Amira, and Alan look up at her. ‘Promise you won’t go anywhere?’ she says.

‘Absolutely,’ Miss Quill says. ‘But if we have to go, we’ll leave the spider as your babysitter, seeing as you think it perfectly safe.’

‘Just stay there, would you?’ Tanya says, jumping across the slats to the boxes of documents. She tries to lift one. Far too heavy, so instead she pulls at the cardboard the box is resting on. The cardboard tears away, leaving the box where it is.

‘Change of plan,’ Tanya says, popping her head back out the hatch. ‘I’ll pass big piles of paper down.’

Miss Quill shrugs. She’s standing at the front window, watching the workers. ‘You’d better hurry. I think they’re threatening to finish their tea. It won’t matter once a large metal ball is swinging towards the house.’

‘But you said it was this afternoon,’ Tanya says.

‘I said that Constantine Oliver told me it was this afternoon. Hardly a reliable source.’

Tanya scoops up a thick layer of papers and hands them to Alan who’s waiting at the top of the stepladder. She goes back, grabs some more, and repeats till they yell at her to stop. Amira sits cross-legged on the floor, going slowly through her pile; Miss Quill and Alan have a bed each to work on. Miss Quill has laid hers out systematically; Alan, not so much.

Tanya stays in the attic. It feels different up here now, as does the whole stone house. The cobwebs, either thrown up by the spider or one of its tiny, non-bony relatives, now feel like the tie-dyed sheets her aunt swagged up on the lounge ceiling ‘to make it cosy’. She sits on a dusty blanket and reads documents by torchlight. Most of them are Alice’s old bills and bank statements. Many of the bills were red ones, which is odd because most of the bank statements showed a ridiculously healthy balance that kept going upwards due to interest rates that Tanya hadn’t known went that high. Alice had hardly spent anything, other than on bills and deliveries of tinned orange food.

A door slams downstairs. Heavy, booted steps cross the hallway, louder than the click-click of the spider’s spinnerets.

‘They’re coming back in,’ Tanya says.

‘What should we do?’ Alan asks.

‘Keep going,’ Miss Quill says.

‘They won’t find us easily,’ Amira says. ‘The bone spider is throwing its fine web over us.’

‘Like an Invisibility Cloak?’ Alan says. Tanya can hear the geek in his voice from up here. She smiles. She feels the same way.

‘If they properly search in here, though, they’ll find us,’ Amira says.

‘We can scare them first though, right?’ Alan asks.

‘Absolutely,’ Miss Quill says. There’s something in her voice, too—Tanya can hear it. It might even be a smile.

For the next half an hour, the shuffling of paper, the occasional sigh, and the tapping of the bone spider’s legs is all that can be heard. Tanya, having gone through her first pile of documents, takes out a shoebox covered in decoupage flowers: forget-me-nots, dandelions, roses.

As she opens an envelope, Alan whispers up to her, ‘I’ve got something that could be useful.’

Tanya moves across the beams then lies flat out along the cardboard, looking down at them through the hatch. She waves at Amira.

‘What’ve you got?’ Tanya asks.

‘Shh,’ says Miss Quill, ‘keep your voice down, would you? Do you want us to be found?’

Alan holds up a plastic folder. ‘A file of documents from around the time of Alice Parsons’ death. I’ve found a copy of her death certificate and a list of instructions to the undertaker.’ He keeps his voice very quiet.

‘What’s on the list?’ Tanya whispers back.

‘She wanted an open casket wake in this house, but nobody was to be invited.’

‘I like the sound of Alice,’ Miss Quill says.

‘After the funeral, her coffin was to be taken to the family vault in Kensal Green Cemetery, the tomb to be left open due to her long-term fear of premature burial.’

‘Very sensible,’ Miss Quill says, nodding.

‘How is that, in any way, sensible?’ Tanya says.

‘If you’re ever buried ten metres underground on a hostile planet with only a toothpick and a straw to save you, you’ll know how stupid that question is.’

Tanya shakes her head. ‘Anything else, Alan?’

He looks down the list. ‘She wanted flowers from the garden on top of the coffin and, now this is interesting, she asks if they can locate her daughter to inform her of Alice’s death. There’s an asterisk there, and underneath a note saying “delicacy is required, as my daughter does not know me”. And a key, to the vault maybe.’

‘That’s so sad. So she did have a daughter,’ Tanya says. She thinks of all those dolls in the room of unblinking eyes.

‘It says here the daughter was adopted,’ Alan continues.

‘There’s a certificate attached. “Unwed”, it says. Alice Parsons gave birth to a baby girl, Catherine Grace Parsons, November 11, 1959. Catherine was adopted by a couple from Stoke Newington. They may have changed her name afterwards.’

Miss Quill’s phone rings. It’s Charlie. ‘Yes, yes, of course I’m fine,’ she whispers. ‘We’ve found Tanya. And a dream-making alien spider.’ She pauses, listening. ‘No, you don’t need to come. Yes, really. Now go and amuse yourselves until we get back.’

Footsteps tramp up the stairs. ‘Did you hear a mobile go off?’ one of the workers shouts.

‘Keep the noise down, will you?’ Tanya whispers to Miss Quill. ‘Do you want us all to be found here?’

‘Shut up,’ Miss Quill replies. Tanya retreats into the attic. The men walk down the corridor towards them.

‘Could’ve sworn I heard a ringtone up here,’ he says.

‘That’s the least of it, Doug. I wouldn’t have come back, only he told me I wouldn’t be paid at all if I didn’t. I saw some weird stuff earlier. From what I heard, something dodgy happened here,’ a second man says.

‘What, like a murder or something?’ Doug says.

‘Yeah. Or worse.’

‘Worse than murder?’ Doug doesn’t sound convinced. Tanya sticks her head out of the hatch and pulls a face at Amira.

‘Alright, maybe not worse, but really bad. I can’t even tell you what I saw.’

‘Have you been through everything up here?’ Doug says.

‘Don’t know if there’s any point. I’ve searched downstairs and there’s nothing we can sell. There’s a load of creepy dolls that I wouldn’t give to a charity shop and a TV that hasn’t been turned on since 1985.’

‘I know the feeling.’

They’re standing right outside the slightly open door. Tanya lifts her head back up. They walk in. She closes her eyes, as if that’ll help in any way at all.

‘I mean, look what’s in here,’ Doug says. ‘Dodgy old furniture that’ll collapse if we move it, filled with an old woman’s knickers. Not my ide

a of fun. Anyway, once Oliver gets here, it won’t matter. He’ll give the nod and this house’ll be a pile of smashed stone before dinnertime.’ His voice fades slightly as if he’s turning away.

Footsteps back out onto the hallway floorboards. The door closes.

‘Right,’ Tanya says, head popping out of the attic again like an upside-down Whac-a-Mole. ‘We don’t have much time. Someone needs to stay here to look after the bone spider and work out where we can relocate her.’

‘Where would that be?’ Alan asks.

‘No idea,’ Tanya says. ‘Nightmares aren’t welcome anywhere.’

‘And where are you going?’ Miss Quill asks.

‘I’m going to find a baby bone spider,’ Tanya says. ‘Who’s going to drive me?’

‘I will,’ Alan says, standing up.

‘Do you want to come too?’ Tanya asks Amira.

Amira shakes her head and looks back down to the papers on her lap.

‘OK, then,’ Tanya says. ‘But you should both look out for Constantine Oliver and his wrecking ball.’

FORTY-FIVE

THE LOST LETTERS

Tanya sits in the front of Alan’s MINI. A box of letters is on her lap.

‘Do you think Amira’ll be okay?’ she asks.

‘Why wouldn’t she be?’ Alan asks, eyes on the road. He flinches as a lorry drives past.

‘She doesn’t know Miss Quill. And you know how she can be quite . . .’

‘Brusque? Sharp? Rude?’ he says. Each of the words brings a bigger smile to his face. ‘She doesn’t mean it really.’

‘She doesn’t?’ Tanya says, incredulity soaked into her voice like rum in black fruitcake.

‘Oh no. It’s just her way,’ Alan says.

‘Have you seen her any other way?’ Tanya asks.

Maybe she acts differently with other adults, on her own. Maybe she’s let Alan in on a different Quill.

‘Oh no,’ Alan says. ‘That would be strange.’ Poor Alan.

He squints at a road sign. He’s gone the wrong way already. ‘Amira will be safe with Miss Quill. I don’t know much about what’s happened to her, but the stone house has been her refuge for the last weeks. It’s probably the safest place she’s been in for a long time.’

‘Even with the nightmares?’ Tanya asks.

‘We carry our nightmares with us,’ Alan says. ‘The spider spins them outside of your body, but they’re still there, walking behind you wherever you go.’

‘I’m so glad you said you’d take me, Alan,’ Tanya says, looking out of the window. ‘You’re a ray of hope in a dark, dark world.’

‘Thank you,’ he says shyly. She’s glad now that he didn’t pick up on the sarcasm.

They’ve hit a traffic jam. It feels like the MINI is moving an inch at a time. Tanya opens the box of letters and looks inside the top envelope. She reads through it in silence, then breathes out when she reaches the end. She flicks through all the envelopes in the box.

‘They’re letters Alice wrote to her daughter. Never sent.’ She feels like crying. The tale of several lives in a sorrow of letters.

‘What does the first one say?’ Alan asks.

‘I’ll read it out,’ Tanya says. She composes herself then begins.

My daughter, my darling Catherine, Happy birthday!

It’s been ten years since I saw your face, but I remember it as if you were next to me now. Your hair was so black. Your eyes were bright blue, but I’ve been told that babies’ eyes change in the first weeks of their lives. They could be brown now. I remember your little fists held up to your chin and your tiny lips blowing bubbles.

I was told that it was a bad idea to have a photograph, as it would cause me to have more of an attachment to you. I wish I hadn’t listened. Please believe me, Catherine, I wish I hadn’t listened to any of them. If I had a photo of you as you are now, I’d look at it every day and think of you. I don’t know your face, you see. I’ve heard friends say about their children they were allowed to keep, that they have ‘their nose’ or ‘their eyes’, but I’d never say that about you. You have your nose and your eyes. I wouldn’t recognise you if I saw you in the street. Secretly, though, I hope you’ll look up one day and see me in the window. Or I’ll look up one day and see you in yours. And we’ll know.

This is your birthday. I can’t help imagining what you’re doing, who you’re with. I made you a cake! I had the ingredients sent here, as I don’t like to go out, just in case you come to find me. I know it’s silly, but waiting for you is the least I can do. The cake is on the dining room table, where I’ve put all the comics I’m keeping for you. A real sweep. All these characters and heroes swing through my letter box every week and I pretend I’m reading to you even though you might be a bit grown-up for that now.

I have a house! Your Nonna and Grandpops left this house to me, but I still can’t forgive them. If you find me, then there’d be plenty of room for you. You can pick your own room, of course, but there’s one that I’m reserving for you. It’s on the top floor and looks out over both the front and back gardens. You can see miles of sky in that room.

It was Bonfire Night last week and I opened the window and watched as fireworks squealed across the night, writing their signatures in bright ink and smoke. I know you’d have loved it. In those last days of my pregnancy, I went to a Guy Fawkes Night and you wriggled around and turned inside me like a Catherine wheel. That’s when I gave you your name. I don’t even know if that’s your name any more, but you will always be Catherine to me.

Happy birthday again, darling Catherine

Your mum, Alice

xxx

Alan rubs his knuckle under his eye, removing a tear. They don’t speak for a few minutes.

‘Hell,’ says Tanya, at last.

‘Yeah,’ Alan says.

‘There’s more,’ Tanya says, looking through them all. None of them has been opened, none sent to the adoption agency on the envelope. How was Catherine supposed to find Alice if she’d never received them?

‘I’m not sure we should be looking at them,’ Alan says. ‘It feels too private.’

‘But what if we can help?’ Tanya says. ‘Maybe we can find Catherine, or whatever her name is now.’

‘Adoption or family breakup is very complex,’ Alan says. ‘It’s not going to be a case of Happily Ever After. Alice won’t get her reunion.’ He looks older suddenly, as if pain had moved in.

‘If I can help a family get back together, even if it’s after someone’s died, then I will,’ Tanya says.

‘Are you sure this is about Alice and Catherine?’ Alan asks gently.

‘Who else would I be talking about?’ she asks, then, quickly, before he can answer, continues. ‘She talks about the bone spiders here. That might be able to help us.’

Dearest Catherine,

Something amazing has happened. It’s not your birthday yet, but I had to write and tell you. Are you afraid of spiders? I hope not. I’ve always liked them. They keep flies away and help me feel I’m not alone. I thought I’d seen really big spiders, until last week. Remember me telling you that I couldn’t keep up with the cobwebs anymore, and that I’d been having really bad dreams? Turns out it wasn’t my illness. It was the bone spider. I caught her reflection in the television screen and screamed. She scuttled away, legs scrabbling on the floor like running knitting needles.

I went looking for her, but she must have covered herself. She can weave webs that hide her, and anyone she chooses to hide. It came in very handy when that developer came round, Mr Oliver. His face is so smooth I’m surprised that smile of his doesn’t fall right off. I watched him look through all the windows and then let himself in the back. He walked around the house like I’d agreed to sell and move into one of his nursing homes, instead of telling him to go away. Only I wasn’t that polite.

I’m getting ahead of myself. I don’t get to talk very much, you see. I kept an eye out for the next few days, and had pretty much decided I’d im

agined her, when I lost my footing on the rug at the top of the stairs and fell. I hit a few of the steps and then found I was suspended in the air between the wall and the banister. I was cradled in a web. Standing at the bottom of the stairs was a huge spider with a distended abdomen, shining white and blinking at me. This arachnid made of bone had saved me from breaking all of mine.

She helped me get out, biting through the web. When I was free, she ran into the corner, head lowered. I walked over and thanked her, touching one of her shoulders. I’m not saying I wasn’t scared, I thought my heart would explode.

She then raised her front legs and you appeared. You were crying in your cot and stopped when you saw me. You smiled, your little cheeks lifting. It was wonderful and terrible. It is the bone spider’s gift to me. I believe she thinks she’s helping. She helps me dream of you all the time, which always makes me happy and always makes me sad.

The bone spider makes the strangest of companions, but that suits me. We even talk, in a way. Yesterday, I asked where she was from, and she started scratching on the hallway floor.

I tried to stop her. ‘That’s good wood,’ I said, then realised that she was sketching. Using her legs as pairs of compasses, she drew circles within circles. When she’d finished, she led me up onto the landing. I looked down and saw she’d drawn a star system completely unlike ours. She pointed to a tiny planet on the outer corners and blinked at me. I didn’t think spiders can cry but it looked to me as if they can.

You probably think I’m mad. I think I’m mad, but at least I get to dream of you when I’m awake.

All my love

Your mum xxx

‘A star system,’ Tanya says, feeling stupid, and she doesn’t like feeling stupid. ‘Of course it is.’

‘It’s not the first thing you’d think of,’ Alan says.

‘The bone spider must have got here through the Rift,’ Tanya says.

‘Through the what?’ Alan looks worried now.

‘It’s a . . . Never mind.’

‘What about refusing to sell to Constantine Oliver?’ Alan says. ‘How did he get hold of the house?’

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

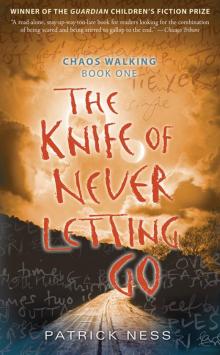

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

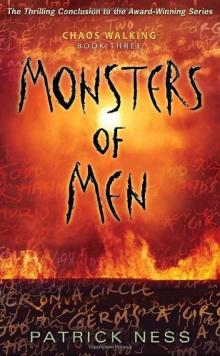

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

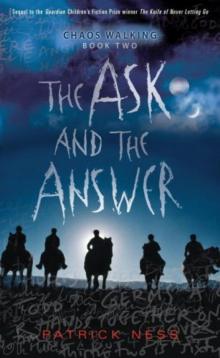

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

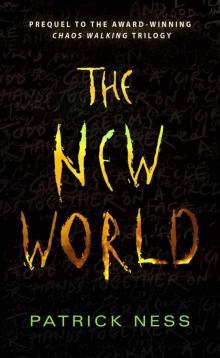

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking