- Home

- Patrick Ness

Chaos Walking Page 17

Chaos Walking Read online

Page 17

One part of the road goes left, the other goes right.

(Well, it’s a fork, ain’t it?)

“The creek in Farbranch was flowing to the right,” Viola says, “and the main river was always to our right once we crossed the bridge, so it’s got to be the right fork if we want to get back there.”

“But the left looks more travelled,” I say. And it does. The left fork looks smoother, flatter, like the kinda thing you should be rolling carts over. The right fork is narrower with higher bushes on each side and even tho it’s night you can just tell it’s dusty. “Did Francia say anything about a fork?” I look back over my shoulder at the valley still erupting behind us.

“No,” Viola says, also looking back. “She just said Haven was the first settlement and new settlements sprang up down the river as people moved west. Prentisstown was the farthest out. Farbranch was second farthest.”

“That one probably goes to the river,” I say, pointing right, then left, “that one probably goes to Haven in a straight line.”

“Which one will they think we took?”

“We need to decide,” I say. “Quickly now.”

“To the right,” she says, then turns it into an asking. “To the right?”

We hear a BOOM that makes us jump. A mushroom of smoke is rising in the air over Farbranch. The barn where I worked all day is on fire.

Maybe our story will turn out differently if we take the left fork, maybe the bad things that are waiting to happen to us won’t happen, maybe there’s happiness at the end of the left fork and warm places with the people who love us and no Noise but no silence neither and there’s plenty of food and no one dies and no one dies and no one never never dies.

Maybe.

But I doubt it.

I ain’t what you call a lucky person.

“Right,” I decide. “Might as well be right.”

We run down the right fork, Manchee at our heels, the night and a dusty road stretching out in front of us, an army and a disaster behind us, me and Viola, running side by side.

We run till we can’t run and then we walk fast till we can run again. The sounds of Farbranch disappear behind us right quick and all we can hear are our footsteps beating on the path and my Noise and Manchee’s barking. If there are night creachers out there, we’re scaring ’em away.

Which is probably good.

“What’s the next settlement?” I gasp after a good half hour’s run-walking. “Did Francia say?”

“Shining Beacon,” Viola says, gasping herself. “Or Shining Light.” She scrunches her face. “Blazing Light. Blazing Beacon?”

“That’s helpful.”

“Wait.” She stops in the path, bending at the waist to catch her breath. I stop, too. “I need water.”

I hold up my hands in a way that says And? “So do I,” I say. “You got some?”

She looks at me, her eyebrows up. “Oh.”

“There was always a river.”

“I guess we’d better find it then.”

“I guess so.” I take a deep breath to start running again.

“Todd,” she says, stopping me. “I’ve been thinking?”

“Yeah?” I say.

“Blazing Lights or whatever?”

“Yeah?”

“If you look at it one way,” she lowers her voice to a sad and uncomfortable sound and says it again, “if you look at it one way, we led an army into Farbranch.”

I lick the dryness of my lips. I taste dust. And I know what she’s saying.

“You must warn them,” she says quietly, into the dark. “I’m sorry, but–”

“We can’t go into any other settlements,” I say.

“I don’t think we can.”

“Not till Haven.”

“Not until Haven,” she says, “which we have to hope is big enough to handle an army.”

So, that’s that then. In case we needed any further reminding, we’re really on our own. Really and truly. Me and Viola and Manchee and the darkness for company. No one on the road to help us till the end, if even there, which knowing our luck so far–

I close my eyes.

I am Todd Hewitt, I think. When it goes midnight I will be a man in twenty-seven days. I am the son of my ma and pa, may they rest in peace. I am the son of Ben and Cillian, may they–

I am Todd Hewitt.

“I’m Viola Eade,” Viola says.

I open my eyes. She has her hand out, palm down, held towards me.

“That’s my surname,” she says. “Eade. E-A-D-E.”

I look at her for a second and then down at her outstretched hand and I reach out and I take it and press it inside my own and a second later I let go.

I shrug my shoulders to reset my rucksack. I put my hand behind my back to feel the knife and make sure it’s still there. I give poor, panting, half-tail Manchee a look and then match eyes with Viola.

“Viola Eade,” I say, and she nods.

And off we run into further night.

“How can it be this far?” Viola asks. “It doesn’t make any logical sense.”

“Is there another kind of sense it does make?”

She frowns. So do I. We’re tired and getting tireder and trying not to think of what we saw at Farbranch and we’ve walked and run what feels like half the night and still no river. I’m starting to get afraid we’ve taken a seriously wrong turning which we can’t do nothing about cuz there ain’t no turning back.

“Isn’t any turning back,” I hear Viola say behind me, under her breath.

I turn to her, eyes wide. “That’s wrong on two counts,” I say. “Number one, constantly reading people’s Noise ain’t gonna get you much welcome here.”

She crosses her arms and sets her shoulders. “And the second?”

“The second is I talk how I please.”

“Yes,” Viola says. “That you do.”

My Noise starts to rise a bit and I take a deep breath but then she says, “Shhh,” and her eyes glint in the moonlight as she looks beyond me.

The sound of running water.

“River!” Manchee barks.

We take off down the road and round a corner and down a slope and round another corner and there’s the river, wider, flatter and slower than when we saw it last but just as wet. We don’t say nothing, just drop to our knees on the rocks at water’s edge and drink, Manchee wading in up to his belly to start lapping.

Viola’s next to me and as I slurp away, there’s her silence again. It’s a two-way thing, this is. However clear she can hear my Noise, well, out here alone, away from the chatter of others or the Noise of a settlement, there’s her silence, loud as a roar, pulling at me like the greatest sadness ever, like I want to take it and press myself into it and just disappear forever down into nothing.

What a relief that would feel like right now. What a blessed relief.

“I can’t avoid hearing you, you know,” she says, standing up and opening her bag. “When it’s quiet and just the two of us.”

“And I can’t avoid not hearing you,” I say. “No matter what it’s like.” I whistle for Manchee. “Outta the water. There might be snakes.”

He’s ducking his rump under the current, swishing back and forth until the bandage comes off and floats away. Then he leaps out and immediately sets to licking his tail.

“Let me see,” I say. He barks “Todd!” in agreement but when I come near he curls his tail as far under his belly as the new length will go. I uncurl it gently, Manchee murmuring “Tail, tail” to himself all the while.

“Whaddyaknow?” I say. “Those bandages work on dogs.”

Viola’s fished out two discs from her bag. She presses her thumbs inside them and they expand right up into water bottles. She kneels by the river, fills both, and tosses one to me.

“Thanks,” I say, not really looking at her.

She wipes some water from her bottle. We stand on the riverbank for a second and she’s putting her water bottle back into he

r bag and she’s quiet in a way that I’m learning means she’s trying to say something difficult.

“I don’t mean any offence by it,” she says, looking up to me, “but I think maybe it’s time I read the note on the map.”

I can feel myself redden, even in the dark, and I can also feel myself get ready to argue.

But then I just sigh. I’m tired and it’s late and we’re running again and she’s right, ain’t she? There’s nothing but spitefulness that’ll argue she’s wrong.

I drop my rucksack and take out the book, unfolding the map from inside the front cover. I hand it to her without looking at her. She takes out her torch and shines it on the paper, turning it over to Ben’s message. To my surprise, she starts reading it out loud and all of sudden, even with her own voice, it’s like Ben’s is ringing down the river, echoing from Prentisstown and hitting my chest like a punch.

“Go to the settlement down the river and across the bridge,” she reads. “It’s called Farbranch and the people there should welcome you.”

“And they did,” I say. “Some of them.”

Viola continues, “There are things you don’t know about our history, Todd, and I’m sorry for that but if you knew them you would be in great danger. The only chance you have of a welcome is yer innocence.”

I feel myself redden even more but fortunately it’s too dark to see.

“Yer ma’s book will tell you more but in the meantime, the wider world has to be warned, Todd. Prentisstown is on the move. The plan has been in the works for years, only waiting for the last boy in Prentisstown to become a man.” She looks up. “Is that you?”

“That’s me,” I say, “I was the youngest boy. I turn thirteen in twenty-seven days and officially become a man according to Prentisstown law.”

And I can’t help but think for a minute about what Ben showed me–

About how a boy becomes–

I cover it up and say quickly, “But I got no idea what he means about them waiting for me.”

“The Mayor plans to take Farbranch and who knows what else beyond. Sillian and I–”

“Cillian,” I correct her. “With a K sound.”

“Cillian and I will try to delay it as long as we can but we won’t be able to stop it. Farbranch will be in danger and you have to warn them. Always, always, always remember that we love you like our own son and sending you away is the hardest thing we’ll ever have to do. If it’s at all possible, we’ll see you again, but first you must get to Farbranch as fast as you can and when you get there, you must warn them. Ben.” Viola looks up. “That last part’s underlined.”

“I know.”

And then we don’t say nothing for a minute. There’s blame in the air but maybe it’s all coming from me.

Who can tell with a silent girl?

“My fault,” I say. “It’s all my fault.”

Viola rereads the note to herself. “They should have told you,” she says. “Not expected you to read it if you can’t–”

“If they’d told me, Prentisstown would’ve heard it in my Noise and known that I knew. We wouldn’t’ve even got the head start we had.” I glance at her eyes and look away. “I shoulda given it to someone to read and that’s all there is to it. Ben’s a good man.” I lower my voice. “Was.”

She refolds the map and hands it back to me. It’s useless to us now but I put it back carefully inside the front cover of the book.

“I could read that for you,” Viola says. “Your mother’s book. If you wanted.”

I keep my back to her and put the book in my rucksack. “We need to go,” I say. “We’ve wasted too much time here.”

“Todd–”

“There’s an army after us,” I say. “No more time for reading.”

So we set off again and do our best to run for as much and as long as we can but as the sun rises, all slow and lazy and cold, we’ve had no sleep and that’s no sleep after a full day’s work and so even with that army on our tails, we’re barely able to even keep up a fast walk.

But we do, thru that next morning. The road keeps following the river as we hoped and the land starts to flatten out around us, great natural plains of grass stretching out to low hills and to higher hills beyond and, to the north at least, mountains beyond that.

It’s all wild, tho. No fences, no fields of crops, and no signs of any kind of settlement or people except for the dusty road itself. Which is good in one way but weird in another.

If New World isn’t sposed to have been wiped out, where is everybody?

“You think this is right?” I say, as we come round yet another dusty corner of the road with nothing beyond it but more dusty corners. “You think we’re going the right way?”

Viola blows out thoughtful air. “My dad used to say, There’s only forward, Vi, only outward and up.”

“There’s only forward,” I repeat.

“Outward and up,” she says.

“What was he like?” I ask. “Yer pa?”

She looks down at the road and from the side I can see half a smile on her face. “He smelled like fresh bread,” she says and then she moves on ahead and don’t say nothing more.

Morning turns to afternoon with more of the same. We hurry when we can, walk fast when we can’t hurry, and only rest when we can’t help it. The river remains flat and steady, like the brown and green land around it. I can see bluehawks way up high, hovering and scouting for prey, but that’s about it for signs of life.

“This is one empty planet,” Viola says as we stop for a quick lunch, leaning on some rocks overlooking a natural weir.

“Oh, it’s full enough,” I say, munching on some cheese. “Believe me.”

“I do believe you. I just meant I can see why people would want to settle here. Lots of fertile farmland, lots of potential for people to make new lives.”

I chew. “People would be mistaken.”

She rubs her neck and looks at Manchee, sniffing round the edges of the weir, probably smelling the wood weavers who made it living underneath.

“Why do you become a man here at thirteen?” she asks.

I look over at her, surprised. “What?”

“That note,” she says. “The town waiting for the last boy to become a man.” She looks at me. “Why wait?”

“That’s how New World’s always done it. It’s sposed to be scriptural. Aaron always went on about it symbolizing the day you eat from the Tree of Knowledge and go from innocence into sin.”

She gives me a funny look. “That sounds pretty heavy.”

I shrug. “Ben said that the real reason was cuz a small group of people on an isolated planet need all the adults they can get so thirteen is the day you start getting real responsibilities.” I throw a stray stone into the river. “Don’t ask me. All I know is it’s thirteen years. Thirteen cycles of thirteen months.”

“Thirteen months?” she asks, her eyebrows up.

I nod.

“There are only twelve months in a year,” she says.

“No, there ain’t. There’s thirteen.”

“Maybe not here,” she says, “but where I come from there’s twelve.”

I blink. “Thirteen months in a New World year,” I say, feeling dumb for some reason.

She looks up like she’s figuring something out. “I mean, depending on how long a day or a month is on this planet, you might be . . . fourteen years old already.”

“That’s not how it works here,” I say, kinda stern, not really liking this much. “I turn thirteen in twenty-seven days.”

“Fourteen and a month, actually,” she says, still figuring it out. “Which makes you wonder how you tell how old anybody–”

“It’s twenty-seven days till my birthday,” I say firmly. I stand and put the rucksack back on. “Come on. We’ve wasted too much time talking.”

It ain’t till the sun’s finally started to dip below the tops of the trees that we see our first sign of civilizayshun: an abandoned water mill at the river

’s edge, its roof burnt off who knows how many years ago. We’ve been walking so long we don’t even talk, don’t even look around much for danger, just go inside, throw our bags down against the walls and flop to the ground like it’s the softest bed ever. Manchee, who don’t seem to ever get tired, is busy running around, lifting his leg on all the plants that have grown up thru the cracked floorboards.

“My feet,” I say, peeling off my shoes, counting five, no, six different blisters.

Viola lets out a weary sigh from the opposite wall. “We have to sleep,” she says. “Even if.”

“I know.”

She looks at me. “You’ll hear them coming,” she says, “if they come?”

“Oh, I’ll hear them,” I say. “I’ll definitely hear them.”

We decide to take turns sleeping. I say I’ll wait up first and Viola can barely say good night before she’s out. I watch her sleep as the light fades. The little bit of clean we got at Hildy’s house is already long gone. She looks like I must do, face smudged with dust, dark circles under her eyes, dirt under her nails.

And I start to think.

I’ve only known her for three days, you know? Three effing days outta my whole entire life but it’s like nothing that happened before really happened, like that was all a big lie just waiting for me to find out. No, not like, it was a big lie waiting for me to find out and this is the real life now, running without safety or answer, only moving, only ever moving.

I take a sip of water and I listen to the crickets chirping sex sex sex and I wonder what her life was like before these last three days. Like, what’s it like growing up on a spaceship? A place where there’s never any new people, a place you can never get beyond the borders of.

A place like Prentisstown, come to think of it, where if you disappeared, you ain’t never coming back.

I look back over to her. But she did get out, didn’t she? She got seven months out with her ma and her pa on the little ship that crashed.

How’s that work, I wonder?

“You need to send scout ships out ahead to make local field surveys and find the best landing sites,” she says, without sitting up or even moving her head. “How does anyone ever sleep in a world with Noise?”

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

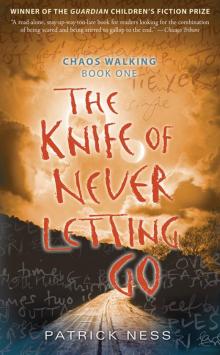

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

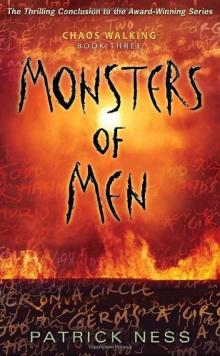

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

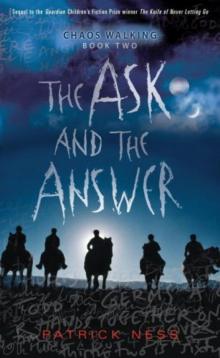

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

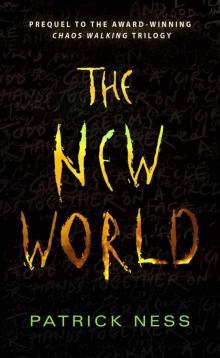

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

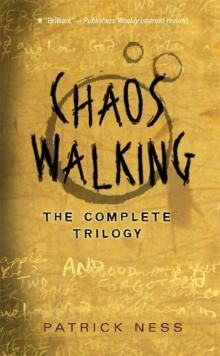

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking