- Home

- Patrick Ness

And The Ocean Was Our Sky Page 2

And The Ocean Was Our Sky Read online

Page 2

The hand held out a disc only slightly smaller than itself, as if presenting it.

But presenting it to whom?

“It is round,” I said. “Gold.”

“A coin?” suggested Treasure.

“More,” the Captain demanded. “Tell me more.”

“There are symbols on it,” I said. “Three upward triangles. Perhaps mountains?”

“I did not ask for analysis, I asked for description.”

“A cross-mark along the bottom,” I swiftly added. “A crooked line next to it.”

The Captain was silent. Then she spoke only a single word, “Move,” and she was already swimming to a distance to start her run. I sped away from the ship as fast as I could, and even then she only just missed me as she slammed into the hull, so violently the ship cracked right in two. After such power, she seemed to merely shrug the rest of the ship to pieces.

The wood surrounding the hand floated free, revealing the young, terrified, very much alive man it belonged to, still grasping the disc, shackled to a board from the hull that was now dragging him to his death.

We watched him drown for a moment before the Captain astonished us by issuing a breather bubble from her blowhole that surrounded the young man’s head, giving him air.

“Captain?” I asked, shocked.

“The lines you described at the bottom are not symbols,” she said, circling the man in the water as he struggled to the surface of the Abyss. A simple push of her tail was enough to tumble him back toward us. “They are letters in man language. T and W.”

Willem returned, swimming close to me as this sunk in. Even Treasure swam near, we three Apprentices bound in fright at what our Captain was suggesting.

Until it moved past suggestion into fact.

“We have found,” the Captain said, “the trail of Toby Wick.”

8

EVEN BY THAT POINT, EVEN THAT EARLY ON, I had already killed many men, but I had tried to avoid this destiny.

Though I was never asked my own feelings about my grandmother’s prophecy that I would hunt, I had accepted it with a hardness the younger me would have wrongly called maturity. Like all whales, I hated men, and with good reason: their bloody killings, their sloppy, wasteful harvesting proving that they killed as much for sport as for need. They purported to dominate the sea while being able to stick only to the under-surface of the Abyss, threatening our great pods and cities from its margins.

I hunted because our cities needed hunters. And as I’ve said, by the time I reached my Apprenticeship, I had my own reasons, too. But even as my grandmother prophesied my fate those years before, my willingness still contained one small rebuke. There was one part of the hunt, the unspoken part, the superstitious part, that I would not join in. My mother and grandmother had raised me to be what my grandmother was and what she’d hoped my mother would be.

“I cannot only be a hunter,” I said. “I am also a thinker. I will not join their religion.”

“You will,” my grandmother said, making it both command and inevitability.

“I will not. Fools and brutes, suffocating on superstition, worshipping their devil–”

“Do not say his name,” my mother suddenly joined in. “Do not speak it.”

“Why?” I taunted. “Bad luck? The devil will come to find you if you speak his name aloud?”

This, I must admit, was the bravado of youth, proclaiming separation from my old-fashioned elders. But I was more prescient than I knew.

“I will hunt, but I will not be a fool.”

“Daughter of mine, do not say it.”

But I did.

“Toby Wick,” I said. More than once, perhaps even relishing the pain on my mother’s face, the distaste on my grandmother’s. I named our devil. Our monster. Our myth.

But who is the fool? I said his name, and now I had found him.

9

THE YOUNG MALE BECAME OUR PRISONER, though in his first panic, he nearly drowned. The bubble breather is a reservoir of air we developed from a chemical in flatfish that extends oxygen use and another we discovered in coral that helps the bubble keep its shape. Even so, it’s a shock to take a first breath while still underwater. I wouldn’t have even been sure a man could master it, if I had ever thought of such a ridiculous notion. This one, at least, was struggling.

“Where is he?” our Captain demanded of him, her tongue thick with the language of men, one all hunters learn though it is stupendously difficult.

The young male was surprised, to say the least, to hear a great Captain of a whale, fifty times his size, five hundred times his weight, speak in his own language, though the words stretched as they traveled across water rather than air. He struggled again against his breather, swallowing water, coughing, swallowing more, not knowing which way was up in this space he was never meant to live. Honestly, how did these creatures ever think they were fit to sail upon the great ocean?

“Take him to the surface,” the Captain said to me.

I was startled. “The surface?”

She rounded on me. “Have we become a crew where the Captain must issue every order twice? Take him to the surface.”

I needed no further reminder. I took the terrified young man in my mouth – which only terrified him more – and swam to the surface of the Abyss, rolling upside down to enter the world of men.

10

I LET HIM GO INTO HIS PRECIOUS AIR. He only coughed more and thrashed at the water. I stayed there with him, unsure what to do after following my Captain’s command.

At the very least, I could breathe deeply.

Ah, the Abyss. The dizzying moment when your weight shifts, and the world tilts, up becoming down, the world pulling at your stomach like a gyroscope, and suddenly, there is air to breathe.

We are proud, proud creatures of the ocean. We dominate it, conquer it, there is no creature in it that doesn’t flee before us or do our bidding. It is the supreme element, three full dimensions in which to live and race and hunt. We have illuminated its darknesses, husbanded its fish. We have made great cities, grown out from the mountaintops that drop from our sky.

We are the ocean.

And yet, still, the Abyss holds our life. We must breathe. We must. Even with the breather bubbles, we must, all of us, return to the Abyss now and again.

This is our weakness.

The young male struggled his way to a bit of wreckage. He clung on, gasping at the air, while I breathed directly and considered the riddle we had discovered.

The ship was still afloat, but there were dead men in the water. No other pods were in evidence who might have done that, and they certainly would have harvested the bodies before scuttling the ship. And here was the young male, hand stuck into the water, with a message meant for . . . who, exactly? Any hunting pod who happened by?

Or one in particular?

Captain Alexandra, as I said, was famous and infamous. She was known as the hardest-driving, most risk-taking Captain to sail from our ports. This reputation was well-earned. She was a veteran of a thousand hunts. Her Apprentices – the ones who did not die on the Abyss – rose to the highest ranks of their own hunting pods.

I had fought tooth and tail to be chosen as even her humblest Apprentice. If I was going to hunt, I was going to hunt with the best. But that’s the risk, isn’t it? Being the best gives you nowhere to go but down. It also makes you a target, for if someone else wants to be the best, they have to beat you, don’t they?

And perhaps, in the Captain’s mind, that included the best hunter men had to offer.

“Bathsheba!” the Captain called from what was now below me. “Has he recovered?”

“He recovers from his drowning,” I answered. “I don’t know if he will ever recover from his fright.”

“Not my concern. Give him another bubble and bring him back. We will have words, the man and I.”

She swam back to our ship, now almost fully stocked from the salvage. Even the remnants of their hull wer

e being reclaimed by our sailors, where its wood would be used for repairs. Waste nothing at sea, for it is sometimes a desert and you never know where replenishment may come.

I circled the young male. He still, remarkably, held the disc in his hand, as if he’d forgotten it in his shock. He watched me, his eyes wide. I opened my mouth to bring him back–

“No, please!” he shouted.

I was so surprised to be addressed directly I paused. Men rarely bothered to speak to us. They never spoke to Apprentices.

“You’re going to kill me,” he gasped.

“Yes,” I said, struggling with the words, “but not yet. Be calm.”

“I didn’t ask for this. I am a prisoner.”

“I am not interested–”

“I’m not a hunter. I never wanted to be a hunter.”

My voice hardened. “Every man wants to be a hunter.”

I took him under, ignoring his pleas.

11

A SURPRISE. I UNDERSTOOD THE YOUNG male best when he spoke.

“Again,” the Captain said, losing her patience.

“He is uncatchable,” the young male said, only just keeping to this side of hysteria. “That’s the message I was to give to you, along with the coin.”

The Captain circled once more, trying to decipher his words. “Again,” she said.

The young male looked at me in a panic. I made to answer, but Treasure beat me to it. “Toby Wick says you’re uncatchable,” she said.

“That is not–” I started to say.

“I’m uncatchable?” our Captain said, sounding pleased.

“Forgive me, Captain,” I said, giving side-eye to Treasure. “The young male says that Toby Wick allegedly calls himself uncatchable.” The Captain looked considerably less pleased with this. “I believe it’s by way of a taunt.”

“She’s wrong,” Treasure said. “Toby Wick knows you’re the best Captain in the sea. It’s a token of respect.”

“Toby Wick isn’t real,” I snapped. “We are being goaded into a chase.”

“Of course we are,” the Captain said. “But that doesn’t mean we can’t explore other meanings.”

“What are you saying to each other?” the young man said, for we were speaking our own language.

“We are discussing your words,” I said to him, without thinking. “What they mean.”

I turned to see the Captain and other Apprentices regarding me. The Captain suspiciously, Treasure jealously, Willem fearfully. “Your facility with languages impresses, Bathsheba,” our Captain said.

“My grandmother was a teacher,” I said, for this was true.

“So she was. You will be our interpreter.”

“Captain–”

“Watch that you make no more mistakes though,” she said, swimming under the ropes that towed the ship. “I heard what the man said. I am uncatchable.” She looked to me, warning in her eye. “That was the message, wasn’t it, Bathsheba?”

What choice did I have? I was an Apprentice. How was I to know this was the first step that would lead everyone here to their deaths?

“That’s right, Captain,” I said. “My mistake.”

“As I thought. Now, find out where we can start the hunt.”

12

THE YOUNG MALE TOLD ME THEY HAD come across none other than Toby Wick and his famous white ship while on their own hunt. Or rather, that is what he gathered, for he saw none of it himself, as he was a prisoner below, for some crime of his own he was vague on. Toby Wick wished to leave a message in the ocean, and he demanded the young male’s ship do it for him.

But something went amiss, something between Toby Wick and the ship’s Captain.

“I heard them screaming,” the young male said. “I heard them dying. Until the Captain himself came down to the brig, made a hole and stuck my hand through. He told me the message I was to give if I survived, but said no more. Then he went above decks and that was the last I heard of him.”

“What happened to him?” I asked. “What happened to the crew?”

“I told you, I don’t know.” He held my gaze, terrified. “But everyone knows Toby Wick is a killer.”

“Toby Wick is a myth,” I said. “You were boarded by a hostile pod, that’s all. Now, tell me about the coin.”

For we had finally prised it from his hand and stored it belowdecks.

“It’s a map,” he told me. “The triangles are mountains.”

“There are many mountains in the ocean,” I said.

“Please,” he said. “I’m cold.”

I stopped, surprised. I considered that he almost certainly was cold. For a man. We had swam up into the depths, far from the surface of the Abyss; I kept needing to enlarge his breather bubble as the pressure made it shrink. Plus, we were moving quickly now, the currents pushing past his body, taking away all its precious heat.

I swam to the Captain, to where she pulled the ship from the front. “He will die if we do not warm him,” I said.

“His life matters not to me. It is the information I want.”

“If he dies, the information dies with him. He has no blubber. He will perish quite soon.”

The Captain sighed. “One heater crab from the hold.” “Two would be better–”

For that, a strike across my head from her tail, enough to jar my teeth together.

“One,” the Captain repeated, needlessly.

I swam, head throbbing, back to the ship, ordering a sailor to bring me a single heater crab. I took it over to the young male, spitting it at his chest. He screamed as it landed on him, but we had bound him to our mast so he couldn’t get away. He didn’t stop screaming until he realized the chemical reaction from the crab’s underside was generating a small warmth.

He gasped inside his breather bubble, shrinking it again. I was forced to fill it once more from my own supply. “You must breathe less heavily,” I said. “Or you will drown.”

“I am upside down but feel right side up. It is very strange.”

“It is the way of this world,” I said. “We feel it when we breach.”

“I have lost my mind,” he said. “This can only be a nightmare.”

“It may be, but you have it in your own power to end it.”

“You mean tell you everything and then die.”

“Yes, that is what I mean. But there are many ways to die. Fast and slow.”

“If a man and a whale speak,” he said, as if it were a well-known saying, “one must perish.”

“Not always. There have been peace talks.”

“Failures. All of them.”

“You hunt us.”

“You hunt us.”

“And so it has always been, and so it always shall be. Now, speak more of your message, and do so quickly.”

The young male seemed, almost all of a sudden, to accept his fate. He breathed a few more times, then he said, “You are to head east-south-east.”

“And who told you this?” I sneered. “Toby Wick himself?”

“Of course not.”

“For Toby Wick is a bedtime story–”

“Someone attacked the ship while I was chained in the hold. Someone bloodied my Captain before he drilled a hole in his own hull.”

“Tell me about the mountains. For my Captain wishes to know.”

“You are to wait offshore of the third.”

“Offshore?” I said. “These mountains reach into the Abyss?”

“The what?”

“Your world. The air below.”

“The air above,” he corrected.

“It’s all a matter of point of view, is it not?”

“That’s what you call where we live? The Abyss?”

“Yes. Is this not known?”

“No, it’s just . . .” He looked around at the ocean passing by, the great deep blues, the cold black heights, lit up here and there by distant floating cities, the stars in our sky. “That’s what we call this.”

“Do you?” I said, genuin

ely startled. “But there is so much life here.”

“Bathsheba!” called the Captain. “Answers!”

I immediately left the young male to tell her what I had learned, but as I went, he said an odd word after me, one I didn’t understand. “What?” I said, turning back.

“Demetrius,” he said. “It is my name.”

I looked at him for a moment longer, this enemy of mine, this prey, this threat to our lives so persistent that our entire culture developed around it, as theirs had around us. This creature I would kill without a thought, or if I did, the thought would be of a reckoning, a balance made of competing currents. This frightened, pathetically small man. A prisoner, first of men, now of us, not even proper crew.

Who said he never wanted to hunt.

I surprised myself by saying “Bathsheba” before I swam away.

13

HERE IS WHY I DID NOT BELIEVE. WHY I knew the myth of Toby Wick to be only that. I will tell you once. It’s all my heart can stand.

The second year of training before you leave on your first hunt is shipbuilding, for who knows when an Apprentice might be called upon to aid a sinking whale-ship? The shipbuilding bays – swathes of open water near common men-ship graveyards, from which we reap most of our material – were distant from my home city, and to travel between, we moved in large pods. Men patrolled their side of the Abyss and we ours, but no one’s safety was guaranteed.

My mother was coming to visit, to see how I was doing. I knew she worried. Her messages only barely concealed it, though even the small attempt at concealment made me miss her.

I had made a small storage-ship (as all trainees did), smaller even than myself, having found every last board on my own in the men-ship graveyard, swimming among the great masted ships men so frequently lost in storms in that part of the sea, their lack of mastery of traveling in weather not even the least useless thing about them. I was proud of my wee storage-ship, eager for my mother to see my progress, maybe even calm her worries some about this destiny I seemed to be following.

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

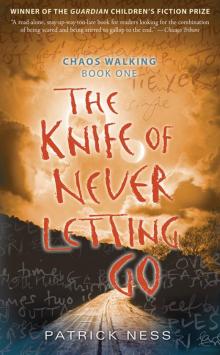

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

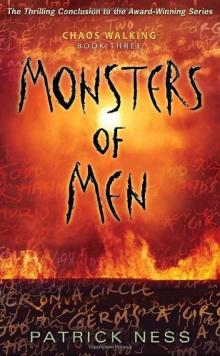

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

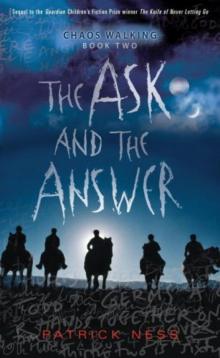

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

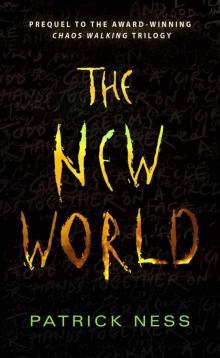

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking