- Home

- Patrick Ness

The Stone House Page 5

The Stone House Read online

Page 5

Thunder claps.

A tempest trapped in an attic room.

‘Move,’ Miss Quill shouts, running back, gathering up April till she’s just about on her feet. ‘Storms never stay in one place.’ She looks over her shoulder with pain on her face, then starts down the stairs, April held close to her. Ram and Matteusz follow.

With a crash, the door flies open. It hurtles towards Tanya and she ducks, twisting her neck to watch it flip over the banister and down to the ground floor. Rain pours from clouds inside the house.

‘I said MOVE!’ Miss Quill shouts. They move.

At the bottom of the first set of stairs, something stands in their way. Someone stands in their way. A girl. Black hair in a bob that stops at her chin, framing what would be her face.

If she had a face.

The front of her head is curved and completely smooth.

No eyes. No nose. No m— Wait.

A mouth appears in the egglike face. It opens. Baby teeth fall out, adult jaws open wide. Screaming comes from lungs far bigger than her thin body can carry.

Her hands reach out. She walks towards Ram, the wind blowing her hair around her like a dark halo.

He runs down the second set of stairs. Tanya slips round the girl and grabs on to Ram’s shirt, keeping close, feeling Charlie hold on to her shoulder. She stops at the bottom, chest heaving.

‘Tanya,’ Miss Quill calls out from some way back. Her voice is steady, slow. A warning.

Tanya turns round.

Her mum is slumped on the floor, her shoulders heaving with silent sobs. She holds her chest as if her heart might fall out. Vivian sees Tanya and her face changes into a snarl. ‘Don’t you come near me,’ she says, getting to her feet.

‘Mum?’ Tanya says.

‘You never gave him a moment’s peace. Did you think he wanted a kid? Really? He did a great job at pretending, I’ll give him that.’

‘It wasn’t my fault,’ Tanya says, faltering.

‘“It wasn’t my fault”.’ Vivian sneers. ‘Pathetic. You take away my love and look what I’m left with. You!’

Tanya reaches for her. ‘Mum, please.’

Vivian holds her hands up and shakes her head. ‘I can’t even look at you, let alone touch you,’ she says and walks towards the stairs. She fades before she gets to the first step.

Charlie puts one arm round Tanya. It’s an awkward hug. ‘That never happened, did it?’ he asks.

‘No,’ she says. ‘I’ve thought it, though.’

‘It wasn’t real,’ he says.

‘Then what was it?’ Tanya asks. She can’t see for tears and rain. ‘What is this place?’

April moans. ‘I don’t feel good,’ she says. She sways. Miss Quill picks her up. Ram stands on one side of her, Matteusz the other. Matteusz takes Tanya’s arm. His eyes are closed. On all sides of them, war begins. Men march with guns. Smoke rises from piles of bones. The crying of rockets. The echo of gunfire. Tents on fire. Agony. Injury. Laughing men and slamming doors.

As they make their way through the haze, Tanya feels something push past her. She turns but can’t even see her hand held out in front of her.

All that can be heard is a web of voices, all caught up in each other:

‘You left us here. You left us for dead. Some of us are still here, Charlie.’

‘You’ll never be best. How could you be? Look at you.’

‘I loved you, Andrea. I’ll never forgive you.’

It’s not even clear if they are voices, feelings, or ghosts. They’re as hard to grasp as the smoke cloaking the house.

The lights of the ambulance flash through the sides of the curtains. ‘Get out,’ Miss Quill says. ‘All of you.’

Tanya goes towards the door then stops. ‘My bag,’ she says, realising it’s no longer across her chest.

‘Leave it,’ Miss Quill shouts, pushing her towards the door.

Tanya twists round and runs back, through the doll room into the kitchen. The bag is on the table. On the counter, where it had been covered in dust, words had been spelled out in alphabet spaghetti:

LEAVE NOW.

FIFTEEN

THE HOUSE IS ANGRY

Doors slam open. Doors slam shut.

I soothe the house, stroke its walls, and tell it that the police and visitors meant no harm. They’re trying to help. It should let me talk to them, not lock me away. It’s keeping me in the attic room as punishment for leaving her a message.

I didn’t dare come out and meet her. I thought she might find me, hoped she would, but then the house made something else happen. It always does. I followed them down the stairs, trying not to take in any of the horror around me. I whispered as I passed her on the stairs. She didn’t see me. Too much chaos. I don’t even know if she heard me.

I don’t like being stuck in a room. The house must know this: It sees one of my nightmares walking with heavy boots across its floorboards. Maybe that’s why it conjures them. It wants me to see them. It must hate me for being here, but then why keep me at all? Why lock all the doors when I try to leave?

At least this time the windows are not painted shut. The webs cover them but I can stick my nose through a hole in the glass to breathe air that does not smell of dust and mould. In that cupboard bedroom, all I had was the corner of a window where I scratched away the whitewash and peered through, down to the street. London carried on as if nothing was happening.

Here though, I have trees outside and a squirrel that I’ve called Yana. Yana twists her head to look at me sometimes. Twitches her nose. The woman reminded me of Yana, both squirrel Yana and my sister. Bright, curious, open. It is difficult to think of my sister, but someone should. There is no one else left to remember her, to remember any of them.

I see her in the house, sometimes. Those are the good days. A few days ago I was in the kitchen making soup when I heard her laugh. I ran into the room of dolls and there she was, on the floor, her legs stuck out. She held a Spanish doll in one hand, an Iranian one in the other, and they were dancing to music I couldn’t hear.

‘Yana,’ I said. She looked up at me, smiled, and disappeared. That was the longest I’ve seen her in a very long time. Most days, I am lucky to catch a glimpse of her sleeve as she runs down the corridor, or smell the fresh lemon drink she loved.

I wish she were in the attic with me all the time. We could play together. I could read to her from this trunk of books. There are 108 books in the trunk. I’ve counted them ten times. They’re a bit young for me, but they would be perfect for her. I was teaching her how to read English before. Even when war was everywhere, we’d sit and read. These books are perfect for me, though, in a way. Stories of horses, ballet shoes, skating shows, an American girl eating apples in attics, boarding schools, and safe adventures with a yellow dog. It’s as if they open a door into a world where hardship is a school bully or losing just one or two of your family members. It feels safe. Comforting. And I haven’t felt safe or comforted in a very long time. I get lost in that world until the house is so cold that I cannot turn the pages anymore.

The house is beginning to calm. Its rages, like thunder, are further apart. It shakes only slightly now. I curl up under the blanket on the bed near the window. At least she came back, that girl. The one from the window. And now I know her name. One of her friends called her it and she has so many friends. Her name is Tanya.

SIXTEEN

MEMORY BOX

Miss Quill waits until Charlie has gone to bed and for quiet to take hold of her house. She then takes out the bracelet from the small box. It is so light it seems to be nonexistent. It is made of an element that carries little mass yet can hold the memories of those it’s bonded with.

It is the red of dried blood. She doesn’t have any photographs that she can look back on; this is all she has. Holding on to the bracelet, she closes her eyes. Snapchats of memories appear and disappear. She’s looked at this so many times but has never shared it with someone else, so how come she saw wha

t she saw in the corridor of the stone house? Who has harvested these memories? And why?

Miss Quill places the bracelet back in the box and locks it in her bedside cabinet. Nothing good can come of this.

SEVENTEEN

DREAMWEAVING

Tanya wakes up, sweating through the thin sheet. She grabs hold of the side of the bed and turns on the light. She looks around. She’s in her bedroom, in her house. Her bedroom is a mess. Clothes have been flung everywhere, books lie in toppled towers on the carpet. It’s exactly as she left it. She dreamed that she was back at the stone house and her mum was trying to turn her to dust, to send her to her dad, she said.

Shuffles down the corridor outside. The door opens. Vivian stands blinking in the doorway. ‘What’s happened?’ she says through a wide yawn. ‘You were screaming.’

‘Bad dream,’ Tanya says.

‘About your dad, like before?’ Vivian says, coming over to sit on the edge of the bed.

‘Kind of,’ Tanya says. She used to have bad dreams where her dad appeared; now Vivian showed up instead. She won’t tell Vivian about the development; it’d upset her too much and when Vivian is upset, the whole house comes to a painful stop.

‘I would give anything to dream about him more often,’ Vivian says. ‘Good dreams, though, not the ones you are having. I don’t want that for you, Tanya.’

‘It’s complicated,’ Tanya says. Dreams about her dad used to start sweet and crisp and turn as bad as the spilled apples in the conservatory. She’s shivering.

‘Yes,’ Vivian says, patting the bed so that she doesn’t sit on any part of Tanya. She shifts closer to her daughter.

‘How could it be different? Your father left us too soon and we are left with memories. It’s hard to make sense of it.’ She takes Tanya’s hand and squeezes it. ‘I know he misses you. I know he is there now, watching over me as I try and bring you up without him.’

Tanya pulls her hand away. ‘Do you really think that’s helpful to me?’

‘It helps me,’ Vivian says.

‘I don’t want him watching,’ Tanya says.

‘You don’t mean that,’ Vivian says, standing up with a groan. Her knees must be playing up again. Tanya feels a sting of guilt at waking her up. Light creeps round the curtains. Vivian’ll have to be up soon for work.

‘I do mean it. I just want to sleep,’ Tanya says, turning over so that she’s facing the other way. It was either that or reach out to her mum, but the ball in her chest won’t let her do that. She did that in her dream and look what happened.

Vivian walks across the room, treading on the creaking floorboard by the cupboard, then walks back. Tanya feels the weight and warmth of a blanket placed on top of her and then a light touch on her head. ‘Sleep well, precious,’ Vivian says. There’s worry in her voice.

‘’Night, Mum,’ Tanya says.

Vivian closes the door softly and shuffles back down the corridor. Tanya’s not sure, but she thinks she hears her crying in the next room.

Tanya leans over and picks up one of the books by the bed. She’ll read through to morning. That’ll stop any more nightmares.

The words run and jump on the page as if playing leapfrog with each other. She’ll just get some rest. Not sleep; she can do without sleep. She’ll lie down and close her eyes for a few minutes. If she stays awake, maybe the bad dreams will stay away.

Tanya feels herself slip into sleep. A dream spins round her. She can’t quite see what’s happening, but it doesn’t matter as she’s wrapped up and warm. She feels something brush behind her and whisper something. It’s a girl’s voice. What is she whispering?

Tanya looks down in her dream. She is wrapped up and warm. In a web that clamps her hands to her legs so that she can’t move. She can’t see the spider that winds it tighter and tighter around her. It’s squeezing the breath out of her lungs, making her exhale every last bit of carbon dioxide. The girl’s voice grows louder, stronger, as Tanya gets weaker. It’s close to her ear now.

‘Wake up, Tanya,’ she says.

Tanya wakes up, sweating. She turns on the light and gets out of bed. There’s no way she’s going back to sleep again tonight.

EIGHTEEN

SENTIENT NIGHTMARES

‘“LEAVE NOW”, laid out on the counter like some kind of Ouija pasta. No wonder you were terrified.’ Ram sneers. They’re outside during break. The indie kids are keeping to the shade, sweating under blue fringes. Three members of the football team kick a ball back and forth, waiting for Ram.

‘Like a séance in a spaghetti factory,’ April replies. She laughs, Ram joins in. Tanya turns away.

‘Tell me you took a photo.’ Ram goes to grab Tanya’s phone out of her hand.

Tanya holds it to her chest. ‘I was trying to get out of the house of horrors at the time, not thinking of Instagram.’

‘You weren’t thinking at all,’ Ram says. ‘You could’ve put it up on the urban myths site, in case anyone had seen the same thing but, oh no, you were too scared. April gets concussion and is back in class the next day, you can’t even investigate properly.’ He shakes his head and goes off with the footballers.

‘We could go back and see if it’s still there?’ April says, watching him leave. It’s hard to tell if she’s serious or not. Sometimes Tanya suspects April of deep levels of irony that even she can’t detect.

‘We might have a problem in going back,’ Tanya says.

‘Why?’ April asks.

‘I went past this morning—yes I know,’ she says as April opens her mouth to speak. ‘It’s not exactly on my way to school. I may have deviated. Anyway, I went past and saw that the workers are all over the front garden, knocking down the back gate to get equipment through. It’ll be hard to just wander in.’

‘They have to go away sometime,’ April says.

‘Not according to this,’ Tanya says, taking out a clipping. ‘Local newspaper this morning.’ She unfolds it.

CONSTANTINE OLIVER LTD. DEVELOPERS SEEKS NIGHTWATCH STAFF AT SHOREDITCH SITE. MUST HAVE EXPERIENCE, REFERENCES AND A SCEPTICAL MIND. [email protected]

‘A sceptical mind?’ April says. ‘Is that normally a requirement for a guard? You’d think a nightwatcher would need to stay awake and have a high boredom threshold, not a strong grasp of the scientific method.’

‘Nightwatcher. I like that,’ Charlie says, walking up behind them. ‘Sounds like the kind of gender-neutral superhero I’d like to be.’

Ding, ding, ding.

They all get messages through at once.

‘Classroom. Now.’ It’s Miss Quill. Usual lack of courtesy or explanation. She’d be terrible at meeting the queen.

(Tanya’s aunt went to meet the queen at a Buckingham Palace garden party. She said the sandwiches were very nice, although a bit thin on the ham, and that the lawn was so green it could be fake, which is the highest praise for her—nothing was so great that it couldn’t be faked better. Her aunt said that when the queen asked her ‘And what do you do?’ she couldn’t think and just answered, ‘Zumba, Ma’am. On Tuesdays at eleven. Come along, if you like. It’s good for the knees. I’ve got spare leggings if you want them.’ The queen seemed keen, but never showed up. Lightweight.)

They move towards the door. When Miss Quill calls, you don’t even question it. When shadows can attack, who knows what’s going on in the classroom at any moment?

The classroom, though, is empty. At least it looks empty. Miss Quill emerges from the stationery cupboard, clutching a pen.

‘I thought I’d lost this,’ she says, holding the pen up high and staring at it like she was checking a diamond for faults. ‘I once signed the death warrant of a king with this.’

‘Finding a pen in a stationery cupboard. That must be the most surprising thing ever to happen to you, Miss Quill,’ Tanya says, sitting down in her usual chair.

‘Sarcasm is beneath you, Tanya. It’s why they call it a “chasm”.’

‘But it’s n

ot spelled—’

‘And it’s probably not just a pen,’ Charlie says. ‘It’s some kind of special device.’

‘Now you’ve made it sound like a dildo, Charlie,’ Ram says. ‘Well done.’

Charlie splutters, trying to cough out a denial.

‘We need to talk about your urban legend site, Ram,’ Miss Quill says, quickly switching focus.

‘It’s not mine, I only—’

‘Found it, yes. But you’ve added to it, haven’t you.’ The last sentence most definitely wasn’t a question. Miss Quill can even out-eyebrow Ram.

He looks away from her gaze, which, to be fair, was one of her uncomfortable ones. Like putting on a scratchy jumper and then being unable to get your head back out of the hole.

Miss Quill brought the site up on the screen and clicked through to the right page. She was right. There were two new entries, the last one put up the night before by ‘Striker’.

‘I don’t know what to be more disappointed by,’ Miss Quill says, ‘the fact that you posted about what happened at the house yesterday without discussing it with us first, or you calling yourself “Striker”. Could you not have chosen something more effervescent in its wit? Have a dash of panache in your online persona, if not your everyday one.’

Ram shrugs. ‘Doesn’t bother me.’

‘What does he say?’ Charlie asks.

Everyone leans forward, trying to read it from the screen.

‘Look it up if you want the details.’ Miss Quill sniffs. ‘The thing I’m interested in is that this wasn’t the first time he posted.’

The others turn to look at him.

‘What?’ he says. ‘Am I not allowed to write online anymore?’

Miss Quill scrolls back to the previous post that went up just before they met up last night. She zooms in and highlights a phrase: ‘Faceless Alice stood in the window. A mouth appeared in her blank face and she started to scream. We could hear her over the rush of the wind, it was chilling. If we hadn’t run then, I don’t know what would’ve happened. My friend was lucky I was there.’

The Rest of Us Just Live Here

The Rest of Us Just Live Here A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls The Crane Wife

The Crane Wife Release

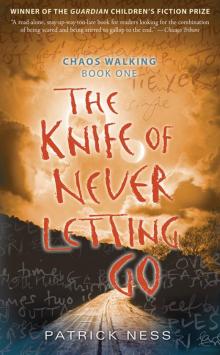

Release The Knife of Never Letting Go

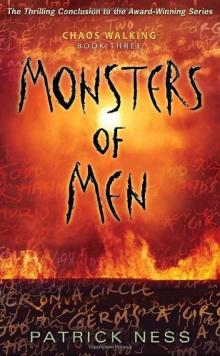

The Knife of Never Letting Go Monsters of Men

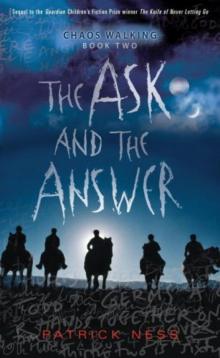

Monsters of Men The Ask and the Answer

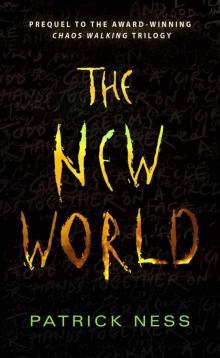

The Ask and the Answer The New World

The New World More Than This

More Than This Burn

Burn The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1

The Knife of Never Letting Go cw-1 Topics About Which I Know Nothing

Topics About Which I Know Nothing And The Ocean Was Our Sky

And The Ocean Was Our Sky The Stone House

The Stone House The Crash of Hennington

The Crash of Hennington Joyride

Joyride What She Does Next Will Astound You

What She Does Next Will Astound You Tip Of The Tongue

Tip Of The Tongue Chaos Walking

Chaos Walking